Professor Odaki Kazuhiko examines the mechanisms behind Japan’s “stunning” and long-running fiscal deficits.

Japan has achieved several “wonders” in the past. It was the first country outside of Europe and the United States to successfully industrialize and join the other developed countries. In the 1980s and 1990s, it became the center of the global high-tech industry and came abreast of the United States in terms of nominal GDP in 1995, albeit for a small number of days.

Thereafter, prices in Japan have not risen for nearly thirty years. Considering the improved quality of many products, this means that prices have been on a downward trajectory. This has never happened in the several hundred years of the world’s economic history.

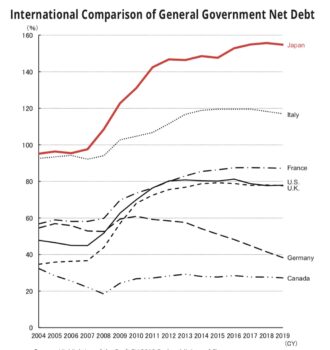

Amidst the wonders of Japan, Japan’s fiscal deficits are stunning. Japan has maintained small tax revenue and large expenditures over several decades. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the national debt was 240% of GDP, much larger than other developed countries, which are around 100%. Japanese people appear to be earnest, but not earnest in terms of fiscal administration.

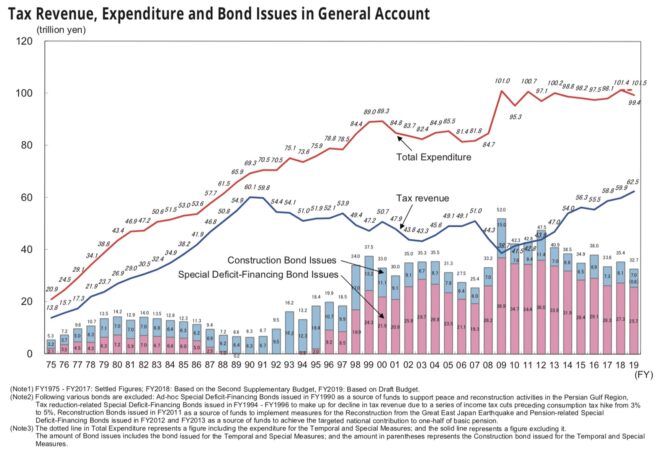

The Japanese economy is managed through aggressive fiscal and monetary policies. Its method is Keynesian, and not classically orthodox. Under the Keynesian model of economic policy, which began in 1966 during the recession that followed the previous Tokyo Olympic Games (1964), the Ministry of Finance issued government bonds to cover the fiscal spending that exceeded tax revenues. Due to the 1972 oil crisis, the 1997 Asian currency crisis and the 2008 global financial crisis, fiscal deficits have further expanded. In recent years, through the Bank of Japan’s proactive monetary easing, an aggressive Keynesian policy has been maintained in both fiscal and monetary policies. In particular, due to the COVID-19 crisis, Japan’s fiscal deficits and monetary easing will likely reach globally unprecedented levels.

For the last twenty years, many economists and spokespersons representing fiscal policymakers and monetary authorities have insisted that these large fiscal deficits are not sustainable and that hyperinflation is just around the corner. In fact, however, prices are falling, a result far from hyperinflation. Additionally, there has been no collapse of government bond prices caused by the mass issuance of government bonds. In contrast, government bond prices have been on the rise, which eventually led to transaction prices exceeding maturity values with negative interest rates.

The mechanism of Japan’s extreme Keynesian policy is as follows. Despite the expansion of fiscal spending due to the aging population and economic crises, tax revenues have not increased. As the government dislikes increasing taxes, fiscal deficits rise and the total outstanding government bonds issued by the Ministry of Finance has reached 1,100 trillion yen. Half of these government bonds have been purchased on the market by the Bank of Japan to be held as assets. The paper money paid for the purchase was deposited with commercial banks and is rarely used. There are few borrowers for this money so the commercial banks deposit this money with the Bank of Japan.

Source: IMF “World Economic Outlook Database” (October 2018) via “Highlights of the Draft FY2019 Budget,” Ministry of Finance, Japan

Hence, both the large volume of bonds issued by the government and the large amount of paper money printed by the Bank of Japan have been withdrawn into the Bank of Japan’s vaults. It is the opposite of a sharp decline in value. Let us assume that the concerns of the economists who used to work for the Ministry of Finance or the Bank of Japan do become a reality, that Japan’s public treasury and the Bank of Japan’s balance sheet are widely seen as discredited, that the value of the yen declines sharply and that hyperinflation occurs, resulting in prices that are ten or one hundred times higher. The Bank of Japan holds 50 trillion yen of assets in the form of stock, real estate and foreign currencies. The Japanese government also owns 1 trillion dollars of US treasury bonds. If the value of the Japanese yen falls to one tenth of its current value, the prices of the foreign currencies and real estate held by the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan would rise in terms of yen, ensuring the soundness of the balance sheets of the Ministry of Finance and the Bank of Japan with correspondingly large profits.

The structure and mechanisms of Japan mean that inflation will not occur, even with several decades of fiscal deficits and abnormal levels of national debt. Accordingly, middle class people tend to hold yen-denominated financial assets; the Ministry of Finance issues government bonds with no burden of interest payment in the zero-interest environment; and the central bank monitors the market to ensure that stable prices are maintained by receiving deposits of paper money it had used to purchase government bonds from private banks without the banks having actively used that paper money.

The mechanism of Japan’s fiscal deficit will likely be maintained for a time, although it may not be sustainable, and the outstanding balance of the national debt is expected to increase.

ODAKI Kazuhiko is a professor at Nihon University and consulting fellow at the Research Institute for Economy, Trade and Industry.

Note: This article first appeared in the Sept./Oct. 2020 issue of the Japan Journal.