Since 2020, the Japanese economy has been shaken by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and increases in food and energy prices triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, recent conditions suggest that the economy is gradually moving beyond the impact of these external shocks. The developments that are especially interesting are the movements in prices and wages. The standard scenario for the Japanese economy in 2023 is that the economy will get back on track for modest growth at a pace slightly above 1%; however, there is a risk that a global downturn will weigh on exports and drag Japan into recession. Japan’s basic monetary policy framework of unprecedented monetary easing is also likely to be revised gradually according to movements in prices.

1. Growth of around 1 percent is forecast

Below is my analysis of the outlook for the Japanese economy in 2023 based on the results of the “ESP Forecast Survey” by the Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER). In this survey, JCER asks for economic forecasts from professional forecasters each month (37 forecasters surveyed in December) and publishes their consensus forecast, giving an insight into the standard forecast scenarios of experts. I will not go into detail, but this consensus forecast confirms a rather positive outlook. According to this forecast, in 2023, the Japanese economy is expected to follow a growth path as shown in Fig. 1. Based on this, the following points can be made about the Japanese economy in 2023.

Source: “National accounts” by Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI), Cabinet Office, from October-December 2022, “ESP Forecast Survey (December 2022)” by Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER)

Firstly, the Japanese economy looks set to move beyond being an economy that is severely shaken by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and to follow a modest growth path, growing at a pace of around 1%. According to the ESP Forecast Survey, the real GDP growth outlook for FY2023 is 1.1%. This is slow compared with other developed economies and Japan will no doubt need to rebuild momentum for economic growth.

That said, there will surely be some sort of tangible sense of economic recovery going forward. Though the economy had been recovering at a modest pace previously, the pace of growth was slow. GDP for April-June 2020 directly after the Japanese economy started being impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic fell by as much as 7.4% compared with October-December 2019. Consequently, even though the economy recovered to some extent after that, growth remained somewhat below pre-COVID levels. It was not until the April-June quarter 2022 that Japan’s economy recovered to pre-COVID levels in a stable manner. The persistence of a situation in which the economy was recovering but had yet to return to pre-pandemic levels prevented any real sense of economic recovery, with households feeling that “income levels have increased but pre-pandemic levels of income were still higher” and companies feeling that “earnings have recovered but are still below pre-pandemic levels.” In 2023, the Japanese economy will continue recovering “with its head above water” so to speak (above pre-pandemic levels) and there will doubtless be a more tangible sense of economic recovery than before.

2. Global slowdown is huge risk

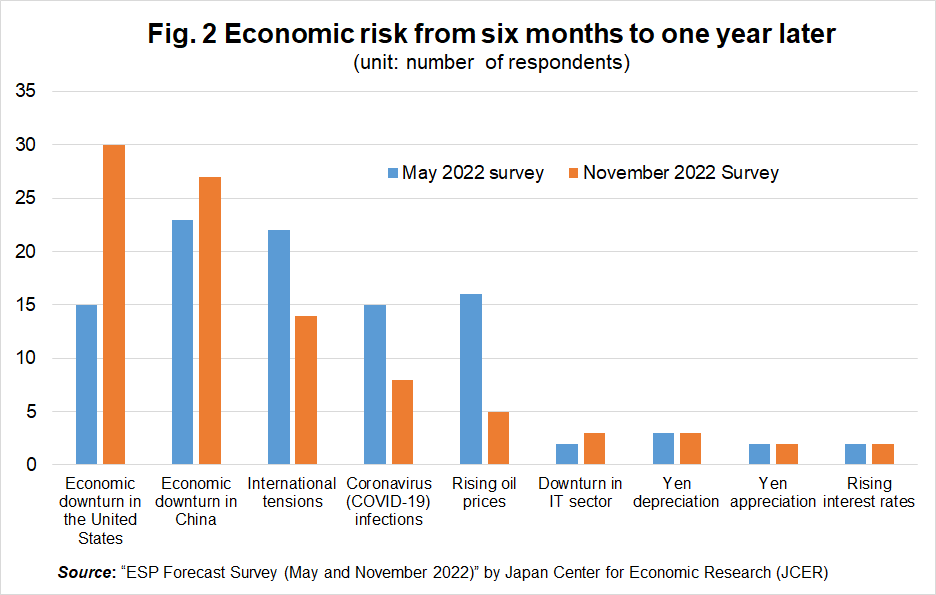

The scenario described above is the standard economic scenario forecast by experts; however, this assumes that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic wear off and there are no more external shocks. It is, therefore, also necessary to consider risk factors which could negatively affect the economy. The ESP Forecast Survey regularly asks professional economic forecasters what they see as risks in the economic conditions outlook. Fig. 2 shows a comparison of their assessment of risk factors in November 2022 with their assessment six months earlier (in May). This comparison indicates the following.

Source: “ESP Forecast Survey (May and November 2022)” by Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER)

Firstly, the risk factors which forecasters attach importance to have changed considerably in the space of just six months. This may be because unexpected external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have emerged one after another. Unexpected external shocks could keep cropping up in the future, but this is difficult to predict.

Secondly, the results show that there is now less awareness of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic as a risk. As of the most recent survey (November 2022), the number of economists regarding COVID-19 as a major risk was one-quarter of those responding “economic downturn in the United States,” which was commonly regarded as a major risk. This indicates the view among economic forecasters that the economy has already entered the “post-Corona” era.

Thirdly, the comparison reveals that economic slowdown triggered by economic downturn in the United States and China has become a major risk factor. Recently, there is growing concern over economic downturn in the United States caused by inflation and interest rate hikes to combat it and China is also experiencing an economic downturn triggered largely by the effects of a zero-COVID policy and the bursting of China’s real estate bubble. It is feared that this would negatively affect Japan’s economy.

I also believe that the risk of global slowdown weighing on exports and dragging Japan into recession is the biggest risk for the Japanese economy in 2023 and that the likelihood of this occurring is fairly high. According to the IMF World Economic Outlook (October 2022), global GDP growth is expected to slow from 3.2 percent in 2022 to 2.7 percent in 2023, and the OECD Economic Outlook (November 2022) also similarly predicts decline from 3.1 percent to 2.2 percent. If anything, it is now common knowledge that the global growth will slow in 2023. On reflection, the situation in which the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine were the major risks to the Japanese economy was an abnormal situation and it is fair to say that there will now be a return to business as usual, so to speak, whereby developments in the Japanese economy will mirror those in the world economy.

3. Movements in prices and wages hold the key

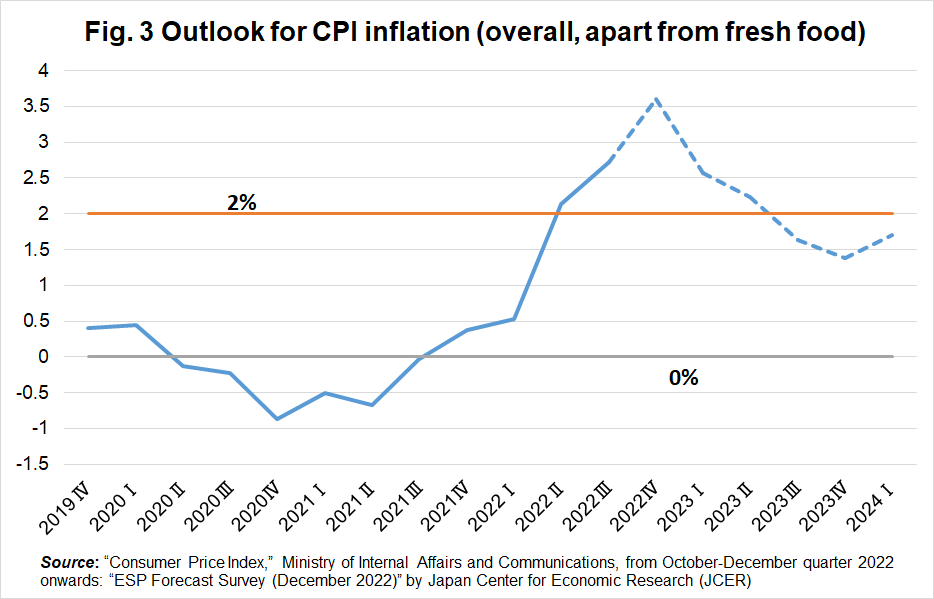

A major point of economic interest in 2023 is what will happen to prices and wages. There are two possible scenarios for prices in 2023: first, the scenario where import price growth slows, causing a return to low inflation, with CPI inflation falling back under 2%, and second, the scenario where inflation stays around 2%.

Many economic forecasters believe the first scenario is most likely. Turning once again to the results of the ESP Forecast Survey, CPI inflation (overall, apart from fresh food) is expected to start falling from a peak of 3.6% in the October-December quarter of 2022 and to be back below 2% from the July-September quarter of 2023, as shown in Fig. 3. The forecasters also put the annual inflation rates at 2.8 percent for FY2022 and 1.7 percent for FY2023.

Source: “Consumer Price Index,” Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, from October-December quarter 2022 onwards: “ESP Forecast Survey (December 2022)” by Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER)

I myself favor the second scenario where the inflation rate stays around 2% in 2023. There are two reasons for this. First, import prices are still in the process of spilling over into domestic prices and I believe that domestic prices will continue being pushed up by higher import prices going forward. This forecast is based partly on the movement in the GDP deflator. In GDP statistics, the domestic demand deflator is a general measure of domestic prices because it summarizes the prices of domestic expenditures. In contrast, the GDP deflator is a measure of domestic inflation because import price inflation is excluded. The movements in the deflators for the July-September quarter of 2022 show that whereas the domestic demand inflator rose 3.2% year on year, the GDP deflator fell 0.3%. The decline in the GDP deflator reflects insufficient pass-through of higher import prices to domestic prices and a decrease in added value. This means there is still scope for pass-through to domestic prices and this situation will continue pushing up domestic prices for some time.

Another factor is rising wages. The Japanese government and Bank of Japan (BoJ) appear to be trying to bring about the pass-through of higher import prices (import inflation) into domestic inflation through wage increases. This strategy is having some success and, with companies also showing understanding, the rate of increase in wages looks set to be comparatively high in 2023.

In such an inflationary environment, the monetary policy of unprecedented monetary easing aimed at delivering a 2% inflation target will no doubt need to be radically reviewed sometime soon. In April 2023, the current Governor of BoJ Kuroda Haruhiko will reach the end of his term, and a new governor will be appointed. This would be the perfect time to review the basic direction of Japan’s monetary policy. In 2023, we will need to keep an eye on monetary policy developments as well as movement in prices.

Komine Takao is a professor at Taisho University

Author’s biography: Born in 1947. Graduated from the University of Tokyo and joined the Economic Planning Agency (currently the Cabinet Office), Japanese Government. Served as Director General of the Research Bureau at the Agency and Director General of the National and Regional Planning Bureau at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Served as Professor at Hosei University from 2003 prior to assuming his current position in 2017. His publications include Nihon keizai no kozotenkan (Structural reform of the Japanese economy), Jinko fuka-shakai (Population onus society), and Heisei no keizai (Economy in the Heisei era) (winner of the Yomiuri-Yoshino Sakuzo Prize).