COVID-19 has had long-term and structural consequences for Japan’s economic society (hereinafter, the Corona Shock). One such consequence is the impact on the population. Since 2020, there have been striking changes in population trends amid the COVID-19 crisis.

By KOMINE Takao, Professor, Taisho University

1. The effect of the Corona Shock on the population

Quite some time has passed since the pandemic began and we are now starting to understand its influence on demographics.

First, there is the decrease in live births. According to the Vital Statistics of the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, there were 812,000 live births in 2021. This is the lowest figure in the postwar period. The population projections (medium-fertility and medium-mortality) published by the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (IPSS) in 2017 have so far been referenced as the standard assumption. According to this standard assumption, live births were forecast to decrease to 886,000 in 2021 and further to 811,000 in 2031 (See Table 1). The fact that the second figure became reality in 2021 suggests that the depopulation tempo in Japan is ten years ahead of the standard assumption.

Table 1: Projected Births, Deaths and Natural Increases: 2016–65 (unit: thousands)

Note: The total population includes foreign nationals.

Source: Population Projections for Japan: 2016–2065 (2017: medium variant), National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

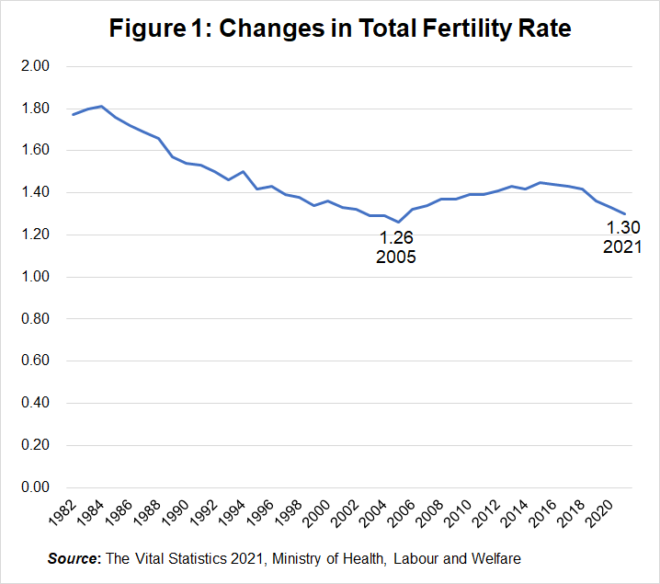

Second, there is the decline in the total fertility rate (number of children born to a woman during her lifetime, or the birth rate). According to the Vital Statistics, the birth rate was 1.30 in 2021, which is the sixth consecutive year of decline, and approaching the lowest postwar level so far (1.26 in 2005) (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Changes in Total Fertility Rate

Source: The Vital Statistics 2021, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

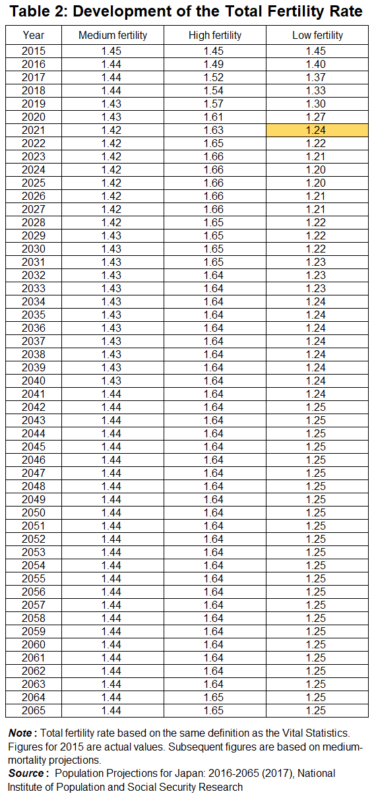

According to the population projections mentioned above, the birth rate should have been 1.42 in 2021. The IPSS population projections present three scenarios (high, medium, and low) for the birth rate, and 1.30 is close to their low estimate (1.24 in 2021) (See Table 2).

Table 2: Development of the Total Fertility Rate

Note: Total fertility rate based on the same definition as the Vital Statistics. Figures for 2015 are actual values. Subsequent figures are based on medium-mortality projections.

Source: Population Projections for Japan: 2016–2065 (2017), National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

Third, there is the decrease in the number of marriages. In 2021, the number of marriages was 501,000, which is a decrease of 24,000 from the previous year. It is also the lowest figure in the postwar period. In Japan, marriage is typically considered a prerequisite for giving birth, so the number of marriages is a leading indicator for live births. We must assume that live births will remain at a low level for a while.

Naturally, in many cases, marriage and childbirth may have been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In that case, the number of births and marriages may increase to some extent once the COVID-19 crisis has passed, but I would have to say that it is difficult to tell what we can expect. It may be difficult to fully recover the numbers of live births and marriages that have been lost.

2. The desired birth rate as policy objective

The accelerating depopulation caused by the COVID-19 crisis is likely to force a major shift in Japan’s population policies. In 2014, the government adopted the 100 million goal for the population. That year, the population of Japan stood at 127 million and the policy goal was to counter the depopulation trend and to halt the slide at 100 million.

In addition, the Outline of Measures for Society with Decreasing Birth Rate, formulated in 2020, adopted a birth rate of 1.80 as its specific target based on measures to counter the declining birth rate. This is referred to as the desired birth rate, which is the birth rate if everyone who wants to get married does so and the number of desired children is fully achieved. There is no doubt that getting as close as possible to the desired rate is preferable, and I think we can all agree to aim for a birth rate of 1.80.

However, the reality is that the birth rate continues to fall. By prefecture, the highest birth rate is 1.80 in Okinawa Prefecture, followed by Kagoshima Prefecture in second place with 1.65. Achieving the target birth rate of 1.80 seems quite difficult. Even if, for argument’s sake, the 1.80 target is achieved, the population will continue to decline because Japan’s population replacement level (birth rate at which the population does not decline) is 2.07.

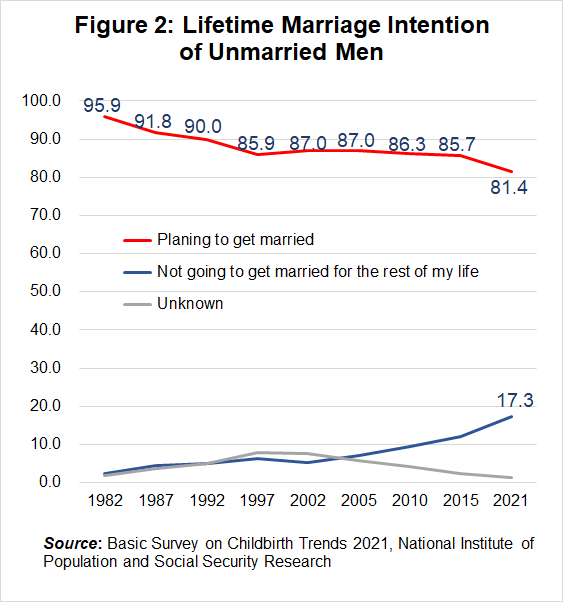

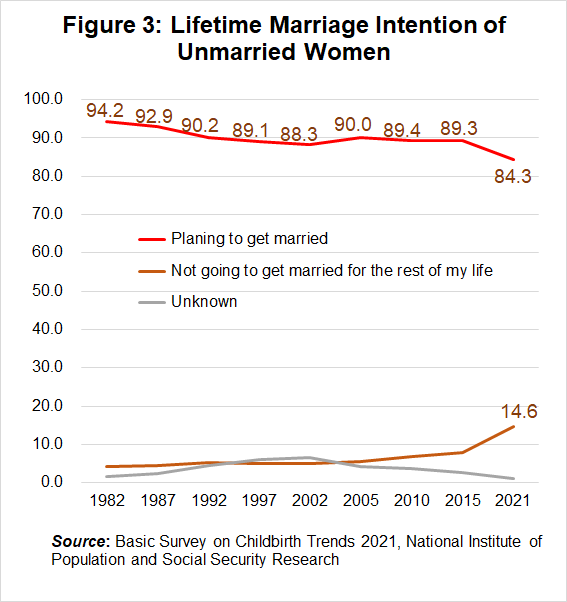

It is even more serious that the desired birth rate itself continues to decline. Looking at the Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends 2021, published by IPSS in September 2022, the following issues are becoming clear in the wake of the Corona Shock. To start with, when single people in the 18–34 age group were asked about their intention to marry, 81.4% of men and 84.3% of women said that they intend to marry someday. This is a considerable decline compared to the previous survey (2015) when 85.7% of men and 89.3% of women said they would marry someday. Meanwhile, the proportion of people who said they have no intention of marrying rose from 12.0% to 17.3% for men, and from 8.0% to 14.6% for women (See Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Lifetime Marriage Intention of Unmarried Men

Source: Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends 2021, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

Figure 3: Lifetime Marriage Intention of Unmarried Women

Source: Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends 2021, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

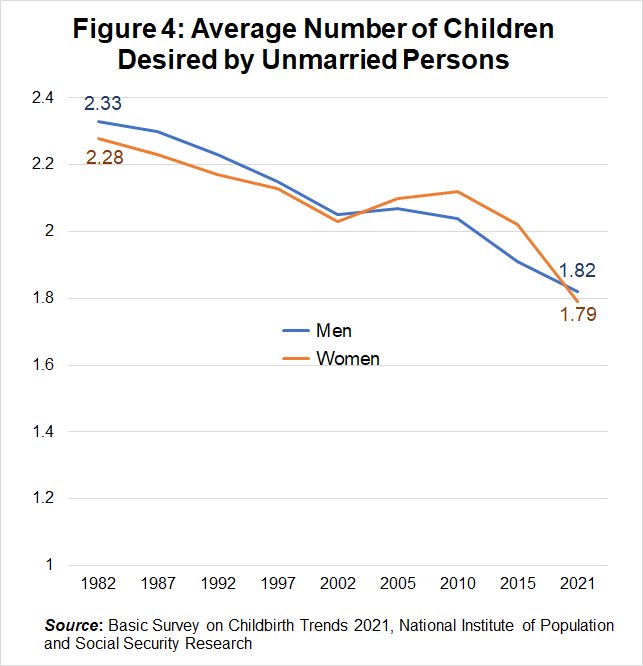

Next, looking at how many children couples would like to have after marriage, the ideal number has dropped from 2.3 to 2.25. There has also been a significant drop from 2.02 to 1.79 in the desired number of children considered by unmarried women (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: Average Number of Children Desired by Unmarried Persons

Source: Basic Survey on Childbirth Trends 2021, National Institute of Population and Social Security Research

Some simple calculations based on these results reveal that the desired birth rate, previously assumed to be 1.80, is highly likely to drop to 1.60. So far, the government has not discussed whether the target birth rate of 1.80 will be retained, or if the target will be adjusted to 1.60 to match the decline in the desired birth rate. In any case, the birth rate is likely to remain at a fairly low level even if people’s hopes for marriage and children are fulfilled 100%.

Both the nation and the regions aim for smart shrink

If we consider the population over the next few decades, the situation will become even more difficult. Many people tend to believe that the birth rate controls population increases and decreases. Given an extremely long time frame, this is correct. However, if the time frame is a few decades, this is not necessarily the case because of the way the depopulation momentum works.

This is how it works. It is not the birth rate, but live births compared to the number of deaths that influence population increases and decreases. Live births are determined by the birth rate and the number of women of child-bearing age. Thus, even if the birth rate changes, there is a time lag before it has an influence on live births. That is the momentum.

For example, since 1975 when the birth rate in Japan settled below 2, live births have been below the number of deaths with the natural population decline starting in 2005. That is a time lag of thirty years. Since women born during a period when the population increases reach childbearing age one after another, the number of women of child-bearing age increases even after the birth rate falls below 2, thus maintaining live births at a high level.

What about today? Since quite some time has passed since live births began to decline, the number of women of childbearing age is already decreasing. When we add in the decline in the birth rate, live births will decrease significantly. This is the present situation. Even if, for argument’s sake, the measures to counter the falling birth rate have an effect and the birth rate increases, live births will not increase and the population will continue to decrease for some time because the negative momentum of depopulation is already at work. To sum up, whether the measures to counter the falling birth rate are successful or not, the population will without doubt continue to decrease for a few decades.

In light of the above, the following are two requirements from a policy perspective.

Firstly, strengthen measures to counter the population decline. The goal should be to raise the desired birth rate. If society as a whole maintains an environment that is friendly to married couples, more people would start thinking about marriage. More married couples would start to think about having children in an environment where employment and child-rearing are compatible. Should we not build policies to both raise the desired birth rate and to achieve the desired birth rate?

Secondly, think about how society can coexist with depopulation. As mentioned earlier, it is difficult to halt depopulation. Consequently, rather than to solve the problem by halting depopulation, it is important to make sure the level of life satisfaction does not decline even if the population decreases.

At the national level, the government should sustain economic growth by aiming to improve productivity to make up for depopulation, build a sustainable social security system premised on depopulation, and adopt more positive immigration policies. Rather than scrambling for generations of childbearing age to increase the population, every region needs to draw up plans to concentrate the population (make more compact) with depopulation as the given condition, and to redevelop social capital into a form that is consistent with depopulation. This is referred to as the smart shrink approach. I believe that we must aim for smart shrink at both the national and the regional levels.

KOMINE Takao

Professor, Taisho University

Born in 1947. Graduated from the University of Tokyo and joined the Economic Planning Agency (currently the Cabinet Office), Japanese Government. Served as Secretary to Chief of the Economic planning Agency, Director of the first Domestic Research Division of the Research Bureau, Councillor for the General Planning Bureau, President of the Economic Research Institute of the Agency, Director General of the Price Policy Bureau, Research Bureau at the Agency and Director General of the National and Regional Planning Bureau at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Has served as Professor at Hosei University since 2003. His publications include Nihon keizairon kogi (Discourse on the Japanese Economy), Heisei no Keizai (Japanese economy in Heisei era), Nihon keizai no kozotenkan (Structural reform of the Japanese economy) and Jinko fuka-shakai (Population onus society).