The “Fermentation Nippon Tourism” exhibition at the d47 Museum in Hikarie, Shibuya, Tokyo

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

A picture of a nose on the clear plastic box invites visitors to lift the lid and sniff what’s inside. I am at the “Fermentation Tourism Nippon” exhibition currently being held at the d47 Museum in Shibuya, Tokyo and getting acquainted with fermented comestibles from all forty-seven prefectures of Japan.

Fugu-no-ransu nukazuke, the fermented ovaries of fugu pufferfish from Mikawa in Ishikawa Prefecture

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

The caption next to the box describes what lies within. Here we have the pickled ovary of a fugu pufferfish, or fugu-no-ranso nukazuke, a specialty of Mikawa on the coast of Ishikawa Prefecture.

The roe of numerous species of fish are widely enjoyed in Japan, most commonly as an accompaniment to rice, but the ovaries and other organs of the pufferfish contain a deadly toxin and, in normal circumstances, are not fit for human consumption.

However, some time several centuries ago the fishermen of Mikawa worked out a way to neutralize the deadly neurotoxin in the large, tasty-looking egg sacs of their prized fugu haul. The method they perfected involves immersing the ovaries in brine for a year or so and then fermenting them for another two years in rice bran (nuka).

This bran-pickling process, known as nukazuke, has long been used throughout Japan to preserve and enhance the flavor, texture and nutritional value of vegetables. In the Hokuriku region of northwestern Japan, of which Ishikawa Prefecture forms a part, it is also used to preserve fish. Pickled mackerel, or saba-no-heshiko, is a specialty of Wakasa in Fukui Prefecture, and is a dish which likely inspired the fishermen of nearby Mikawa in their ovary-pickling pursuits.

Pickles for sale at a greengrocer in Minowa, Tokyo. Nukazuke bran-pickled carrot, daikon giant radish and kabu turnip can be seen in the center.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

A variety of fish eggs, fermented and raw, on sale at a Yokohama fishmonger. Mentaiko (center), fermented and spiced cod roe, is the signature food of Hakata but is widely enjoyed around Japan, typically with rice but also as a dressing for spaghetti.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

I peel back the lid of the plastic box, wiggle my fingers above the old sac of eggs and cautiously lower my head. The smell hits me like a warm, wet beer towel: musty, malty, mellow. Appetizing!

Still, it must have taken the first ovary-picklers of Mikawa some courage to test their recipe. To this day, the precise scientific process by which fermentation detoxifies fugu ovaries is not known, but for connoisseurs of fish eggs it is enough that the wisdom of Mikawa’s ancestors continues to be handed down. The “forbidden delicacy” of Mikawa is said to be so packed with umami it is best enjoyed in the smallest of portions over rice, as a seasoning in pasta or fried rice dishes, or as a topping for ochazuke (rice in hot green tea).

Karasumi, a specialty of Nagasaki, on sale at a dried fish store in Yokohama. Each fermented egg sac on display here retails for close to 10,000 yen.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

It’s a treat I desperately want to try, but although it is available for purchase online, I feel disinclined to place an order. This ingenious creation of the people of Mikawa needs to be enjoyed in its place, looking out over the Sea of Japan, or at an inn in the prefectural capital, Kanazawa, accompanied by a glass of Ishikawa’s famous sake. The Hokuriku Shinkansen, which opened as far as Kanazawa in 2015, could get me there from Yokohama in about three and a half hours.

Fermentation Tourism

Inspiring the urge to travel and find out more about unfamiliar fermented foods is the very goal of the “fermentation tourism” project being led by “fermentation designer” Ogura Hiraku. After graduating from the Tokyo University of Agriculture, Ogura established a fermentation lab in Koshu City, Yamanashi Prefecture, from which base he holds workshops, creates picture books and videos, and advises brewers. Ogura aims to make the invisible microorganisms of fermentation “visible” through design and thereby disseminate Japan’s “culture” of fermentation.

Miso is a form of fermented bean paste made by mashing cooked beans with koji mold, salt, mature miso and other ingredients. There are many different varieties and regional styles. Typically, the longer-fermented misos are used in cooking while the shorter aged misos are enjoyed on their own or as a dip for fresh vegetables. Pictured, a store selling miso in Minowa, Tokyo.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

Characteristic pickles of Kyoto (Kyo-tsukemono): (back) Shiba-zuke — kamonasu eggplant and chopped red perilla leaves; (front) chopped suguki-zuke turnip pickles. Both pickles have a slightly sour taste that derives from salt pickling and lactic acid fermentation.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

It is well known that fermentation lies at the heart of Japanese cuisine, with fermented products such as soy sauce, miso and sake underpinning the umami flavors that define so many dishes, while tsukemono pickles form an essential part of any traditional Japanese meal. But locally produced, often little-known fermented foods also help to characterize the cuisine and culture of individual towns, cities and regions.

In many cases the fermentation recipes were created hundreds of years ago as a means of making the most of surpluses through microbial preservation or, as in the case above, simply making edible precious and perishable local food sources. The unique fermented foods speak of the challenges of the climate and other geographical features peculiar to the sea, mountains, islands and cities that have been overcome by local people, as well as of cultural and religious practices and beliefs such as the mottainai principle of letting nothing go to waste or the non-consumption of animal flesh.

These days natto is fermented on a commercial scale in Styrofoam boxes or paper cups, but it was traditionally fermented in wara straw and is still sold in this form in the Mito area.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

Through the “Fermentation Tourism Nippon” exhibition (until July 8, 2019) and later a book, Ogura aims to draw attention to these unique products and “clarify the importance of fermentation in Japan and the diversity of Japanese food culture, not only from the practical aspect of savor and health but also from the viewpoint of history and spirituality.”

Natto fermented soybeans are distinguished by their slimy, mucilaginous coating and strong, malty aroma

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

The exhibition introduces one representative fermented comestible from each of Japan’s forty-seven prefectures. Items on display include gelatinous mukadenori seaweed from the Nichinan coast of Miyazaki, sour awabancha tea from the mountains of Tokushima, hot yuzu-infused kanzuri red pepper paste from Nagano and the notoriously pungent kusaya fish of Niijima island in the Izu archipelago.

Kusaya, the notoriously pungent delicacy of Niijima, a small island in the Izu Peninsula belonging to Tokyo Prefecture. Mackerel or flying fish is submerged in a unique, repeatedly reused pickling juice and then dried outdoors.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

Most prefectures have more than one unique product of fermentation of which to boast, and curator Ogura had to make some notable sacrifices in his selection. Nagasaki, for example, is represented at the exhibition by the sendango balls of sweet potato paste produced on the island of Tsushima, even while the prefecture is best known as the main producer of one of the “three great chinmi delicacies” of Japan: karasumi, salted and dried mullet roe. (The other two chinmi are raw uni sea urchin roe and konowata, the cured entrails of namako sea cucumbers.)

Kanzuri red pepper paste from Myoko in Nagano Prefecture (let). Togarashi chilli peppers are pickled in salt then scattered on snow for several days to extract some of their heat. The peppers are then blended with rice koji mold and yuzu peel and fermented in barrels for three to six years. Yuzukosho, a similar fermented paste made from green chillies, is a specialty of the the main island of Kyushu but its popularity as a multi-purpose condiment has spread rapidly nationwide in recent years.

THE JAPAN JOURNAL

“[These local recipes] embody spiritual and cultural values widely accepted in the olden days,” writes Ogura on his Campfire crowdfunding page. “They form a part of the breathtaking landscapes, along with their originators and [those] who strive to pass on the highly sophisticated fermentation techniques to the next generation. The selected exhibits form a valuable recollection of ancient wisdom that must not only be retained but also passed on to our future generations [and shared with] people living all around the world in various natural environments.”

Ogura’s words are no mere platitudes. As food traditions around the world become supplanted by homogenized industrial products, engagement is required to stop them disappearing entirely. The sense of urgency is shared by the “fermentation revivalist” Sandor Ellix Katz, whose inspirational 2014 book The Art of Fermentation was a New York Times bestseller and has been translated into Japanese. In the introduction to his comprehensive DIY guide to global fermentation methods, Katz writes:

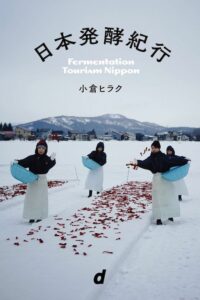

“Fermentation culture is a symbol of each region’s climate and natural features, and kanzuri is the embodiment of that culture,” says Ogura Hiraku. Pictured, the front cover of Ogura’s book published (Japanese only) in tandem with the exhibition.

FROM THE EXHIBITION WEBSITE

Fermentation can be a centerpiece of economic revival. Relocalizing food means a renewal not only of agriculture but also of the processes used to transform and preserve the products of agriculture into the things that people eat and drink every day, including ferments such as bread, cheese, and beer. By participating in local food production — agriculture and beyond — we actually create important resources that can help fill our most basic daily needs. By supporting this local food revival, we recycle our dollars into our communities where they may repeatedly circulate, supporting people in productive endeavors and creating incentives for people to acquire important skills, as well as feeding us fresher, healthier food with less fuel and pollution embedded in it. As our communities feed ourselves more and thereby reclaim power and dignity, we also decrease our collective dependency on the fragile infrastructure of global trade. Cultural revival means economic revival.

Check out the exhibition if you can, and watch this space for news of the book’s release. Ogura hopes to raise enough money to translate and publish his entire findings into English.

Alex Hendy, The Japan Journal