The Shonan region of Kanagawa Prefecture, a short distance southwest of Yokohama, is best known for its beaches and day-trip destinations such as Enoshima, Oiso and Kamakura. Coastal Shonan forms the northern shore of Sagami Bay, with Miura Peninsula to the East and Izu Peninsula to the West. A popular place for surfing and yachting, Shonan’s coastal waters also make for excellent fishing.

Most commercial fishing off the Shonan coast starts at Koshigoe Fishing Port. Small boats set out from here daily to catch fish for the fishermen’s own retail outlets, local markets and shops, and the area’s many seafood restaurants. In addition, charter boats take recreational fishers into the bay to catch everything from octopus to madai (red sea bream), Japan’s delicious “king of fish.”

A typical local fishing boat just off the Shonan coast close to Koshigoe, with the Miura Peninsula visible in the distance. TJJ PHOTO

King of the fish caught off the Shonan coast, however, are shirasu, post-larval and juvenile anchovies (mostly) measuring only one to two centimeters in length. Shirasu school with the rising of the sun, so the fishermen head out at first light to track them down. When a school is identified, these days with the aid of sonar technology, the fishermen lower a net and accelerate away, scooping up the fish in small amounts so as not to damage them before hauling the net aboard.

After sorting the fish and putting them on ice, the fishermen rush the catch back to their workshops for processing. Most of the shirasu are boiled in lightly salted water and partially dried (kamaage shirasu), a process that both changes the flavor and texture of the fish and extends their shelf life. The fish are sold on the same day they are caught under the brand name “Shonan Shirasu.”

An office and restaurant connected to the charter boat Ikeda-maru, which is berthed in Koshigoe Fishing Port just across the road. TJJ PHOTO

In the not-so-distant past, the shirasu fishermen of Shonan would make multiple trips to and from the bay every day, immediately bringing their catch to shore to ensure maximum freshness. Because the distance from the fishing grounds to the local retailers is very short, in the Shonan region it is possible to procure these highly perishable fish in their raw state (nama shirasu), a rare treat anywhere in Japan.

Alarmingly, however, on some days this summer (2025), the fishermen have been returning to port almost entirely empty handed. It is early July, a peak season for the fish, but the familiar 80-gram packs of boiled shirasu are selling for 650 yen each and are rationed to just two packs per customer. Diners now count themselves “lucky” when they find raw shirasu on the menu.

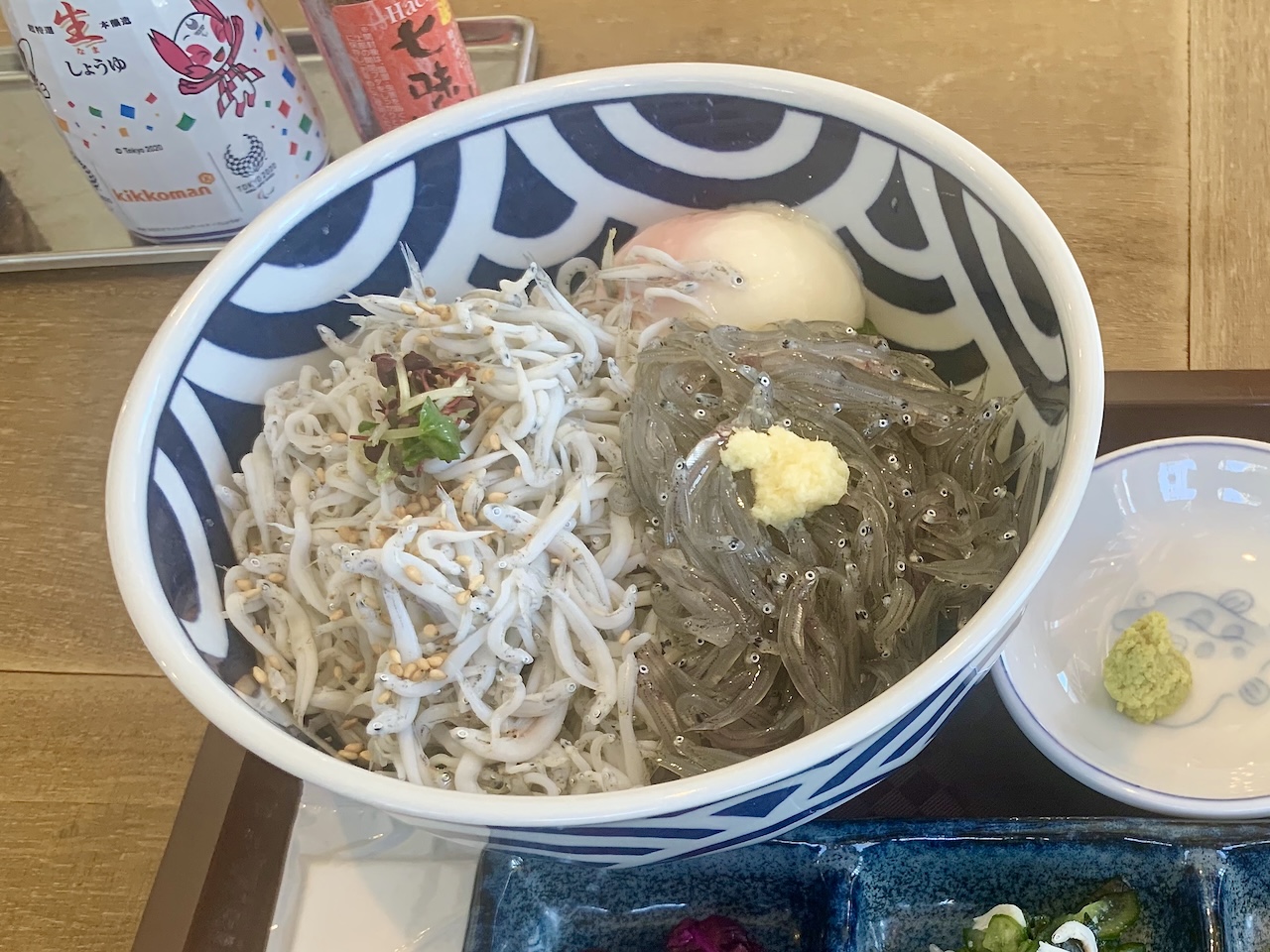

The classic way to eat Shonan Shirasu—raw (right) and boiled shirasu heaped on a bed of rice—as served at Hase Shokudo in Hase, Kamakura City. TJJ PHOTO (2021)

No Fish Today

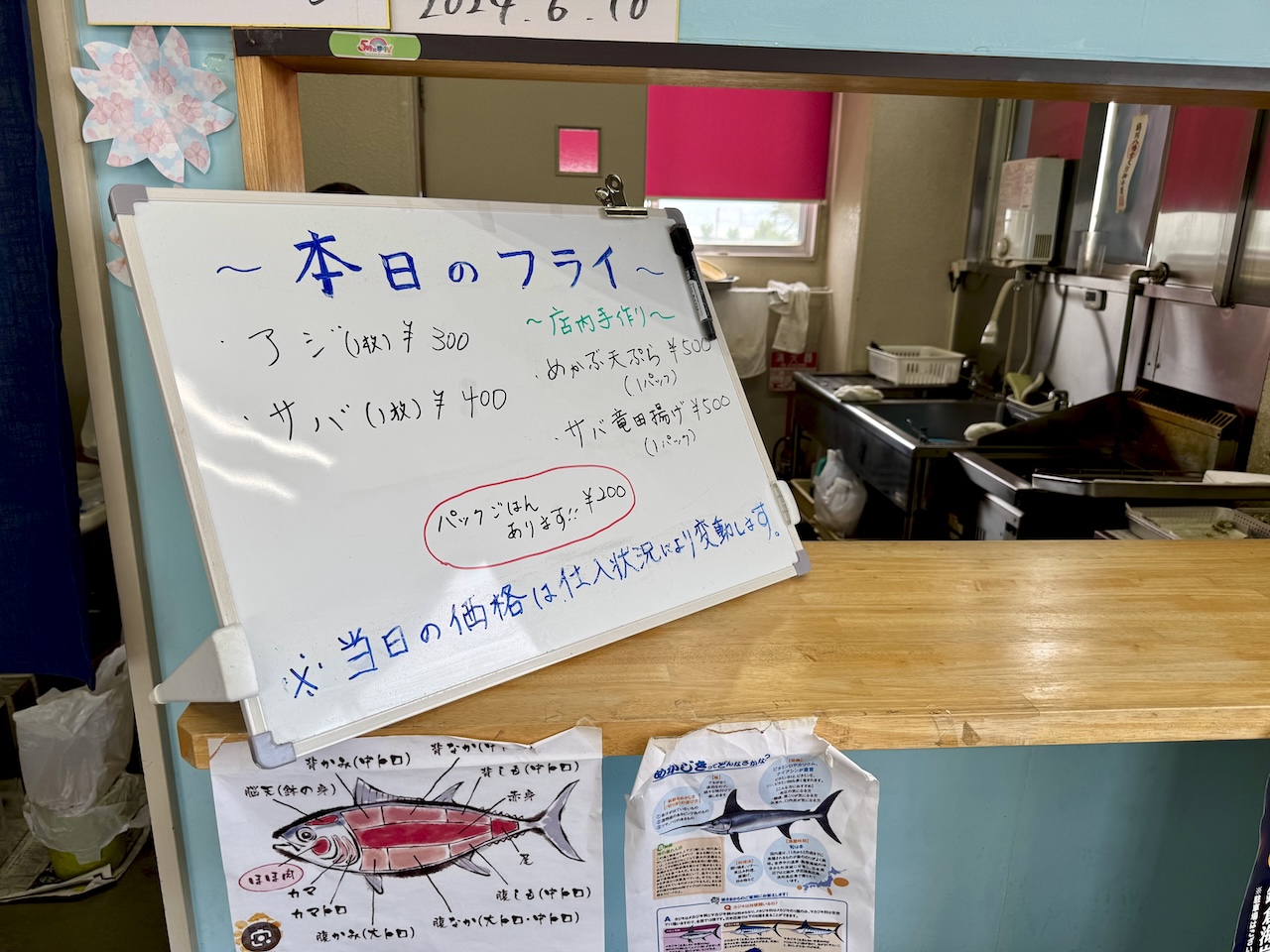

Signs of trouble are evident further up the food chain, too. On a visit to Koshigoe Fishing Port’s Asadore Fry restaurant in early July, I lunched on fresh-fried fillets of morning-caught aji (horse mackerel) and saba (mackerel). The meal was scrumptious as always, but normally at this time of year, the restaurant’s fry cooks tell me, the menu would include fish such as inada (wild yellowtail) and kamasu (barracuda) as well. Owing to warmer waters, they sigh, they don’t have these fish today.

Crisp, light and succulent, fresh-fried fillets of morning-caught aji and saba as served at Asadore Fry. TJJ PHOTO

Decreasing fish catches in recent years, a trend not confined to Sagami Bay, appear to coincide with the Kuroshio Long Meander, which refers to the phenomenon whereby the “black current” that runs from west to east along the Pacific coast deviates from its usual shore-hugging course. The meander causes seawater temperatures and sea levels to rise. The latest meander, which has lasted for seven years and nine months and is by far the longest on record, has been held responsible for a range of recent calamities in Japan.

According to data released in May by the Japan Meteorological Agency, the meander appears to be subsiding, though whether this is good news remains to be seen. The hope is that shirasu, which migrate on the black current, will soon return in numbers close to the Shonan shore.

This feels like wishful thinking, however, and additional measures to guarantee the sustainability of shirasu fishing in Shonan may need to be implemented. The annual ban on the taking of shirasu that runs from January 1 to March 10 is one thing, but presently there is no total or individual quota on the amount of shirasu the local fishermen can catch. Such quotas would be a form of resource management that the local scientific community might help to initiate, monitor and adjust, in the same spirit that volunteers in these parts clean the beaches or conduct neighborhood crime prevention and yomawari fire prevention patrols. The method of finding shirasu has changed with the introduction of useful technologies; science might improve the manner of bringing the fish to shore as well.

Consumers could help the cause too. Shirasu are an important source of food for other fish in the sea, but a luxury for those of us living on the shore. Until we know that stocks have returned, both throughout the anchovies’ growth cycle and in the marine food chain as a whole, we may feel inclined to shun the big shirasu bowl in favor of dishes that utilize the local delicacy more sparingly. Shirasu work wonderfully mixed into omelets, for example, or combined with other ingredients in dishes such as tempura and pizza.

The author’s celebrated shirasu pizza, a cheap four-cheese supermarket pizza sprinkled with onion and boiled shirasu. TJJ PHOTO

Shirasu fishing in Shonan will survive as an essential part of the local food culture, but the shock of the “no fish days” this summer suggests it’s long past time for us all to get creative.

TJJ