In addition to rising energy prices internationally due to the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the continuously weak yen has caused a rise in import prices and thus ongoing import inflation. Professor Komine Takao examines the price situation in Japan and relevant policy issues. The economic data in the text are as of June 15, 2022.

Until now, the Japanese economy has been struggling to get out of deflation. Prices in Japan have been rising at extremely low rates since the early 1990s, when the bubble economy collapsed. The average consumer price index (overall) for 1991–2000 was 0.8%, the average for 2001–2010 is minus 3%, and the average for 2011–2020 0.5%. It was a long-term low inflation rate almost unparalleled in the postwar world economy.

With this low inflation rate, the nominal scale of the economy did not increase, while the added value of companies and the wage income of households also stagnated. Many believed that this deflation was the cause of the long-term slump of the Japanese economy. In January 2013, the government and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) issued a joint statement setting 2% as the target price increase rate, deciding to work to realize it as soon as possible. BoJ Governor Kuroda Haruhiko, who took office in March of the same year, wanted to achieve this 2% in two years and launched easy monetary policies one after another. This included the quantitative and qualitative monetary easing in April 2013, the introduction of a negative interest rate in January 2016, and the Yield Curve Control (YCC) in September 2016. Nonetheless, prices did not rise so much.

However, the 2% target was realized in April 2022. The rate of increase in consumer price index (on the previous year) was 1.2% in March, but it increased to 2.5% in April, thus suddenly exceeding the 2% target. This was because of a reduction in cell phone charges in April 2021, which lowered consumer prices by 1.5% compared to the previous year, the effects of which disappeared in April 2022.

A closer look at consumer prices in April shows that the general index excluding fresh foods (so-called core) had an increase rate of 2.1% and the general index excluding fresh foods and energy a rate of 0.8% In other words, the April rate of increase in consumer price index rose above 2% because of increases in fresh foods and energy prices.

Are the price increases temporary?

Are these price increases sustainable, so that Japan has finally gotten out of the deflation? Or are they temporary, so that Japan will return to a low inflation rate again?

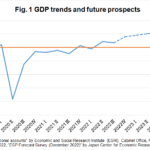

Many economists seem to think it is temporary. The Japan Center for Economic Research (JCER) publishes a monthly survey called the “ESP Forecast.” It surveys the predictions of leading economists and publishes their averages. Looking at the latest June survey, the rate of increase in consumer price index (the general index excluding fresh foods) is predicted to continue to stay above 2% throughout 2022 but gradually decline after that and once again go below 1% from around the end of 2023. They think that when the energy prices stop rising, we will return to a low inflation rate again.

Whether the price increases are temporary or sustainable depends on whether the import inflation turns into domestic inflation. Let us relate this to the movements of three deflators in the GDP statistics. The three deflators are the domestic demand deflator, which indicates changes in domestic prices, the import deflator, which indicates changes in import prices, and the GDP deflator. With regard to the GDP deflator, the import deflator is a negative item, and if the import price increase is the only factor that increases the domestic price, the import deflator and the domestic demand deflator cancel each other out, so the GDP deflator shows zero or a negative value.

The impact of import inflation takes the following path. First, when import prices go up and companies are unable to pass on this cost increase to prices, the import deflator goes up and the GDP deflator goes down. Secondly, when companies finish passing on the cost increase to prices, the domestic demand deflator goes up and the GDP deflator becomes neutral. Then, when wages rise according to domestic prices, so does the GDP deflator.

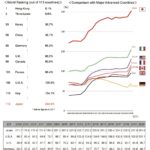

Now, let us take a look at the actual deflator movements (see table). The import deflator has risen significantly from the April–June period in 2021. This is because the rise in energy prices coincided with a weak yen. For a while, however, the domestic demand deflator did not rise much, with the GDP deflator having a bigger rate of decline. This shows that even when import prices rose, companies were not able to sufficiently pass on the costs to prices, keeping domestic prices from rising.

From the October–December period in 2021 to the January–March period in 2022, the domestic demand deflator gradually gained a higher rate of increase, while the rate of decline of the GDP deflator decreased. This indicates that domestic prices started to rise as companies gradually passed on cost increases to prices. If the price increases are limited to this stage and stay within the range of the import inflation, then the price increases will be temporary.

The government is actively calling on companies to raise wages. If wage increases proceed in the future, the GDP deflator will rise and the price increases will be sustainable. The fact that many economists in Japan think the price increases will be temporary, as mentioned above, means that they expect that even if prices rise, wages will not rise accordingly.

Table: Deflator movements (rate of increase on the previous year, %)

| GDP deflator | Import deflator | Domestic demand deflator | |

| January-March 2021 | 0.1 | -1.2 | -0.5 |

| April-June | -1.1 | 15.1 | 0.3 |

| July-September | -1.2 | 19.7 | 0.6 |

| October-December | -1.3 | 27.6 | 1.1 |

| January-March 2022 | -0.4 | 23.3 | 1.8 |

Responding to the price increases

Finally, let us consider how we should respond to such price increases from a policy perspective.

The first thing to consider is that it is almost impossible to prevent import inflation itself. Since Japan relies on imports from overseas for its energy resources, and because they are a necessary commodity, consumption will not decrease immediately just because the prices rise. So, if the energy prices rise, Japan has no choice but to pay. If companies refrain from passing that on to the final prices, they will bear the costs in the form of reduced corporate profits. If companies do pass it on to prices, those prices go up and households pay in the form of decreases in households’ real income. Moreover, if wages rise, that will strain corporate profits again. It is not possible for “everyone to be exempt from a burden.”

The government is subsidizing gasoline distributors in an attempt to limit the rise in gasoline prices.

However, if prices rise, that will be a source of public dissatisfaction. In April 2022, several newspapers conducted polls that showed that out of the policies of the Kishida Fumio administration, the only one that people were dissatisfied with was “price policy.” I think that “even if we are told to do something about the rise in prices, nothing can be done,” but the public does not think so. As such, even in the world of politics, price increases cannot be left unchecked. In particular, since an Upper House election is to be held in July this year, both the ruling and the opposition parties will try to advertise to the public. For example, the government is subsidizing gasoline distributors in an attempt to limit the rise in gasoline prices altogether. Among the opposition, the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan wants to temporarily decrease the consumption tax to 5%, while the Democratic Party for the People also wants to decrease the consumption tax rate until the increase rate of wages goes up as well as provide 100,000 yen as an “anti-inflation allowance” (collected as a tax from high-income earners later on).

I think it is quite futile to try to counter the price increases with government spending in such ways. Given the high household savings rate over the past two years or so, households are not struggling with declining incomes. This might be fine if the price increases come to an end in a very short time, but it will not be possible to handle them with fiscal resources if they drag on. Moreover, as a matter of course, it leads to an accumulation of financial deficit, imposing a large cost burden on future generations. I really hope for this to be reconsidered.

KOMINE Takao

Professor, Taisho University

Born in 1947. Graduated from the University of Tokyo and joined the Economic Planning Agency (currently the Cabinet Office), Japanese Government. Served as Director General of the Research Bureau at the Agency and Director General of the National and Regional Planning Bureau at the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Served as Professor at Hosei University from 2003 prior to assuming his current position in 2017. His publications include Nihon keizai no kozotenkan (Structural reform of the Japanese economy), Jinko fuka-shakai (Population onus society), and Heisei no keizai (Economy in the Heisei era) (winner of the Yomiuri Yoshino Sakuzo Prize).