Of all times to be in Japan, New Year has to be the most pleasurable. In contrast to the preceding week, with its sense of excited anticipation and general bustle as people finish their preparations for Japan’s biggest celebration, a sudden sense of holiday serenity descends as January commences. For great numbers of Japanese, their last meal of the old year will be a simple one of buckwheat noodles—toshikoshi soba—partaken in the fond hope that their fortunes will, like the long noodles, be lengthened and extended. And in many households, the first food of the new year will be the exquisite amalgam of dishes that goes by the name of osechi ryori.

Osechi ryori covers a wide range of seasonal dishes that are eaten at New Year, but it especially refers to the foods daintily arranged in the tiered boxes known as jubako. At one time, New Year was the only time of the year that the mother of the household got a few days’ holiday, and so osechi was developed as dishes that preserve well and could be enjoyed over a period of three days at room temperature. However, the mother being able to enjoy her time away from the stove also meant that she had first to go through the enormous effort of preparing all the various osechi dishes.

In some traditionally minded families, true osechi still has to be made at home. But most people these days opt for the easier option of buying ready-made osechi sets at department stores, supermarkets or even convenience stores. Those wanting to get a good osechi deal may do so by placing their orders three months in advance. For families that really want to go the whole hog, they can pay eye-watering amounts of over 300,000 yen on top-of-the-line osechi at some department stores.

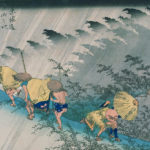

Many of the various dishes that go to make up the New Year fare of osechi ryori have auspicious connotations. DAVID CAPEL PHOTO

The dishes that find their way into the jubako vary from region to region, but many are invested with an appropriately celebratory symbolism for this time of year. Two dishes, however, that are almost certain to appear—often in the uppermost tier of the jubako—are kazunoko and kuromame. Kazunoko is salted herring roe, which in Japanese literally means “number of children,” and the food symbolizes the wish for many offspring. Kuromame are black soybeans that are soaked, boiled until tender and sweetened, and they are thought to be auspicious since mame also means “health.”

However, the reason for these foods having established themselves in the osechi assembly isn’t all down to symbolism. The eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (1684–1751), was a passionate devotee of frugality and austerity. He thought it would be a grand idea if everyone—rich and poor alike—in Japan ate the same simple, cheap foods at New Year, and so he promoted the consumption of then-inexpensive kazunoko and kuromame. The notion that one day some of his countrymen would outrageously splurge over 300,000 yen on luxury osechi would doubtlessly have grieved Yoshimune beyond words.

Many of the other osechi foods are symbolic of health, prosperity and good fortune. Shrimps are thought auspicious because the bowed back of the creature is suggestive of old age and is therefore a symbol of longevity. Sea bream is popular since the Japanese word for the fish, tai, is the final syllable of omedetai (congratulations). The fish-paste cake known as kamaboko usually appears, and it is favored because its pink and white colors have propitious associations.

These days, Western and Chinese foods can also make a showing in osechi sets. And less traditionally minded chefs may feel inclined to enliven and internationalize their osechi boxes with such exotica as fish pie, pastrami, scallop terrine and Swiss roll.

The eating of osechi is traditionally preceded by the quaffing of a special form of spiced sake called otoso, which is believed to ward off sickness in the coming year. And it is somehow appropriate that New Year should begin with a communal drink in this fashion. It is a time when everyone seems that little bit friendlier and more at peace with themselves and the world at large. As one old Japanese saying has it, “Even devils smile on New Year’s Day.”

David Capel is a journalist living in Tokyo.