At some Zen Buddhist temples, vegetarian shojin ryori dishes are elevated to the level of fine art.

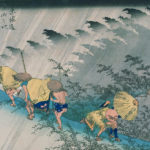

Becoming a Zen monk is hardly the stuff of off-the-cuff decisions. At the stricter sort of Zen monastery in Japan, the first task of an individual with monkish aspirations is to prostrate himself in supplication before the main gate for hours or even days on end. When asked why he seeks entry, the neophyte has to answer that his mind is like a blank sheet of paper ready to be inscribed by his superiors as they see fit. Once inside, the novice will find that rather than some serene cloister detached from all worldly cares, the monastery more resembles a forbidding boot camp, with senior monks displaying all the ferocity of iron-fisted drill sergeants. As the trainee monk undergoes the long process that sets complete annihilation of the self as its goal, he might at least console him with one facet of monastery life: the food’s not too bad.

The vegetarian cuisine known as shojin ryori that is the standard fare at Buddhist temples and monasteries found its way to Japan at the time when that then-newfangled faith was brought to the country’s shores by monks in the sixth century. But it was not until the thirteenth century, with the arrival of Zen, that shojin ryori really spread and found many more mouths to feed.

As vegetarian visitors to Japan can testify, the country is not the easiest place in the world for finding traditional victuals without fish or flesh. Though the number of natural and macrobiotic restaurants is growing in Tokyo and other big cities, vegetarians know to beware that fish-based stocks and other ingredients can often make a surreptitious showing in standard Japanese offerings. However, that is not the case with shojin ryori, which rigidly follows Buddhist strictures against the killing of creatures.

The most obvious feature of shojin ryori is the use of soybean products instead of fish and meat. And it was through the influence of shojin ryori that foods derived from soybeans, such as tofu, began to make a more significant showing in Japanese cuisine along with such vegetable oils as those derived from sesame, walnut and rapeseed.

In addition to meat and fish, shojin ryori avoids eggs and dairy products as well as vegetables with assertive flavors, such as garlic and onions. A key element in Japanese cuisine is the stock known as dashi. However, since the best-known form of this stock is derived from fish, shojin ryori instead prepares its dashi using such ingredients as kelp, shiitake mushrooms and soybeans to lend the appropriate depth of flavor.

Shojin ryori achieves its great appeal through the natural flavors of the freshest of vegetables at their seasonal finest. These are augmented by wild plants from the mountains served with various kinds of seaweed, tofu and such seeds as walnuts and pine nuts. The seasonings are subtle and delicate, with miso and soy sauce lending their accents. Great importance is given to gomadofu, “sesame tofu,” which resembles tofu only in texture and appearance, being actually made after sesame is pulverized with water and the resultant liquid thickened with starch. In Kyoto, yuba (the delicate but highly nutritious skin that forms when soy milk is heated) and the wheat gluten known as fu (made from high-gluten flour, from which the starch is washed away, then mixed with rice flour and steamed) also typically appear in shojin ryori. Above all, no effort is made to try and emulate non-vegetarian dishes. Thus, no “tofu steaks” appear on the menu.

Undoubtedly the best place to sample shojin ryori is at a Zen temple that specializes in providing the fare for visitors. Some Zen temples serve extremely elaborate shojin ryori, and the meals are ones of spectacular sophistication. Though it may seem to the very committed carnivore that the notion of food without meat or fish as well as eggs and dairy products would be dull beyond words, nothing could be further from the truth. The courses are fascinating, inventive, a visual delight, and though shojin ryori might not impel anyone to want to become a Zen monk, it certainly makes you look with entirely different eyes on the merits of non-meaty fare.

David Capel is a journalist living in Tokyo.