2018 marks 150 years since the Meiji Restoration. The Meiji period (1868–1912) was a turbulent time that became a major turning point, signaling the end of samurai rule, and the transition to a modern democracy and industrial modernization. Crucially, it was a time of inclusion and leadership.

Leaders of the Iwakura Mission in London,1872. From left, Kido Takayoshi, Yamaguchi Masuka, Iwakura Tomomi, Ito Hirobumi and Okubo Toshimichi

In October 1867, the Edo feudal government returned power to the imperial court. The Meiji government was established the following year, in January 1868. Pressure had been growing from the 1840s onwards, from western powers coming to Japan with the aim of opening up the country to the rest of the world, and from those looking to put in place a system centered around the imperial court. After a little over 260 years, this brought an end to the feudal government of the Edo period (1603–1867).

Things were anything but easy for the Meiji government to start with. They faced countless challenges, not least revising unequal treaties signed between the Edo feudal government and western forces, dealing with internal conflict with forces loyal to the former shogun, establishing democratic systems, and promoting new industry.

In an effort to confront these challenges, the Meiji government brought in advanced systems from western countries, and also appointed advisors. Having maintained a policy of national isolation for over 200 years however, Japan lacked the necessary human resources for western modernization. Securing and developing suitable human resources therefore became an urgent priority.

In 1871, the Meiji government sent what became known as the Iwakura Mission to Europe and the United States, with the aim of surveying western civilization and conducting preliminary research into unequal treaties. This mission consisted of 107 people, including government leaders and those who had studied overseas. There were five female members of the mission, including Tsuda Umeko, who was aged just six at the time but went on to establish a college for women. The group even included political adversaries loyal to the former shogun, many of whom were also appointed to work under the government. These men included Hara Takashi and Takahashi Korekiyo, both of whom went on to serve as Prime Minister, and Goto Shimpei, who became Minister for Foreign Affairs.

Five women were among the 107-strong Iwakura Mission sent by the Meiji government to Europe in 1871.

There was a good reason for appointing these men. Just over two months after the establishment of the Meiji government, the Charter Oath was issued. The oath called for reconciliation and inclusion, and set out a basic policy for the new Meiji government, including government by the will of the people, governance based on national unity, a society in which everyone is free to pursue their own dreams, and the pursuit of knowledge throughout the world rather than clinging to customs.

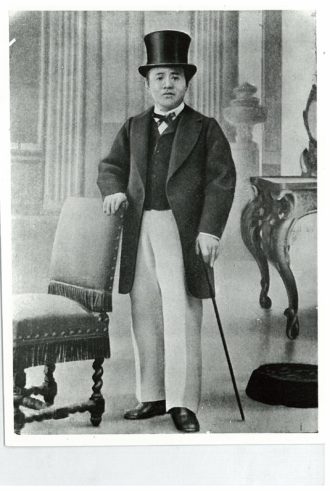

One of the men the government appointed from the ranks loyal to the former shogun was Shibusawa Eiichi, who was later dubbed the “father of Japanese capitalism.” Shibusawa was involved in the establishment of more than 500 companies over the course of his life, and had a hand in over 600 social projects too.

During the final days of the Edo period, Shibusawa worked under Tokugawa Yoshinobu (who went on to become the 15th shogun Tokugawa Keiki). At the time of the Meiji Restoration, he was at the Paris Exposition under the service of Tokugawa Yoshinobu’s younger brother Tokugawa Akitake. During his stay in France, at the age of 27, Shibusawa met a group of Saint-Simonians, who advocated industrial social systems spearheaded by the likes of bankers, merchants and industrialists. He also saw facilities such as orphanages while walking around. These experiences had a knock-on effect on Shibusawa’s activities after returning to Japan.

Having returned home, Shibusawa headed to Shizuoka, where Tokugawa Keiki had been moved, and set up a financial company. With strong encouragement from Okuma Shigenobu, who went on to become Prime Minster, Shibusawa changed course in 1869 and went to work for the Meiji government. He was instrumental in revisions to legislation, including the New Currency Ordinance and the National Bank Ordinance, and in establishing the Tomioka Silk Mill. He resigned from the government over budgetary differences however in 1873, and set up a string of companies, including Shosho Kaisha (now Oji Holdings) and First National Bank (now Mizuho Bank).

Shibusawa Eiichi (1840–1931), the “father of Japanese capitalism”

Shibusawa was also involved in establishing the Tokyo Stock Exchange, and a whole host of companies that still exist to this day, in industries such as cotton, railways, postal services, hotels, architecture, and ship building. He had a hand in setting up institutions including hospitals, colleges for women, and commercial colleges too, putting him at the forefront of those paving the way for development from a private-sector standpoint during the Meiji period. In 1909, Shibusawa visited a number of American cities, as part of a group of some fifty business leaders, to talk about revising unequal treaties and other issues between Japan and the United States. Having met with then US President William Taft, he helped lay the foundations to develop US-Japan relations after that point.

Shibusawa was an entrepreneur who supported countless other entrepreneurs along the way, as well as playing a key role in promoting new industry.

Having established democratic systems, successfully promoted new industry, and persisted in negotiations with the government, Japan’s unequal treaties with western forces were revised in 1911, at the end of the Meiji period.

While the Meiji government made the most of human resources, based on the spirit of inclusion, the private sector helped to lay the foundations for industry, based on new systems.

Just as these pioneers blazed a trail through the Meiji period, Japan has high hopes that young entrepreneurs will step up, and women will play a greater role too, in dealing with the various changes that Japan faces today, 150 years on from the Meiji Restoration.

Mizuno Tetsu is a freelance writer.