As the forest fires rage on in the Amazon, Mizuno Tetsu recalls The Man Who Planted Trees.

There is a book first published in 1953 and since translated into more than twelve languages called The Man Who Planted Trees (French title, L’homme qui plantait des arbres) by French author Jean Giono (1895–1970) who hailed from Provence. I was reminded of this book when French President Emmanuel Macron tweeted about the Amazon rain forest fires on August 22, before the G7 Summit: “It is an international crisis. Members of the G7 Summit, let’s discuss this emergency first order in two days!” In response to President Macron’s exhortation, the G7 raised it as a major item on the agenda, and agreed to provide 20 million dollars in emergency aid.

Giono’s tale is an allegorical work of fiction set in the period between the two world Wars depicting an encounter with a man who plants trees in a desolate, barren part of Provence in the south of France until it regenerates into forest. The Amazon rain forest fires are a reality, and extinguishing them and regenerating the forest will entail great difficulties. However, these difficulties must be overcome for the sake of future generations.

The Man Who Planted Trees was made famous by Frédéric Back (1924–2013), an animator and film director who was also born in France and moved to Montreal, Canada. Back turned the book into an animated film in 1987, receiving the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film. Following the release of the animated film, tree-planting became popular in Canada, and the number of trees planted that year was more than eight times that of previous years.

In 1989, the book was published in translation as a picture book with illustrations by Back. When it was introduced in the book review section of the media, many adults purchased it to read to their children. It was the peak of the bubble economy and a boom time for books on self-discovery and self-improvement. The picture book appealed to adults seeking to connect with society, elevate their spirit, and polish their education, so they would purchase it either for themselves or as a gift for friends or acquaintances. The book also came to be used as a teaching material for moral education in schools.

Later, the Japanese version of the animation was released, and The Man Who Planted Trees was still popular by the time the Great Hanshin-Awaji Earthquake struck in 1995. This was the worst urban disaster since the Second World War, and volunteers from all over Japan rushed to the scene. That year was called the first year of volunteerism, and led to volunteer activities becoming firmly established in the minds of Japanese people. This may be attributed to the traditional Japanese spirit of mutual support and Japanese people’s experience of community service, as well as the fact that many adults had purchased Back’s picture book.

Tree Planting Pioneers

When I participated as a volunteer in thinning activities in the Greater Tokyo Metropolitan Area in the late 1990s, not only the representatives of the sponsoring NGO but many of the participants too were well-acquainted with Back’s picture book. Similarly, many representatives of environmental NGOs were strongly influenced by the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the Earth Summit).

One aspect of these thinning volunteer activities symbolizes the situation of forests in Japan, many of which are planted. Unlike natural forests that are sustainable even if left alone, man-made forests plant single species such as Japanese cedar and cypress at a high density, making management measures such as removal of undergrowth, improvement cutting, thinning and lopping essential. However, sluggish domestic timber prices and a dwindling forestry industry workforce resulted in the devastation of planted forests, further lowering the value of timber and making large-scale landslide disasters caused by typhoons and heavy rains more likely to occur. Volunteers who want to do something to help address such problems take part in activities to maintain planted forests.

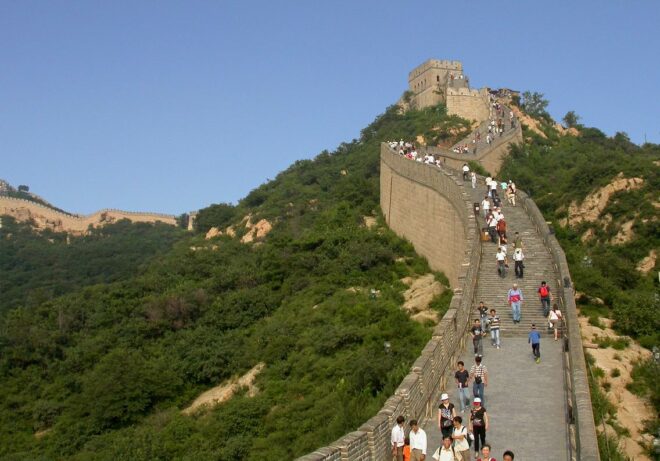

Many people plant trees to protect traditional crafts; many fishermen have resolved the problem of a declining catch by going to the mountains and planting trees; and many NGOs and companies are engaged in tree planting activities both in Japan and abroad to protect the global environment. One pioneer is Toyama Seiei (1906–2004), an agriculturalist who successfully greened 20,000 hectares of desert in China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, transforming it into farmland. In recognition of his achievement, the Chinese government erected a statue of him, the only person other than Mao Zedong to be immortalized in this way during his lifetime. Miyawaki Akira, Professor Emeritus, Yokohama National University, is a plant ecologist who has planted more than 40 million trees in more than 1,700 locations in Japan and overseas. In particular, he is known for his successful greening activities along the Great Wall of China and the regeneration of a Malaysian rainforest, which was said to be impossible.

In 1998, Miyawaki Akira of Yokohama National University led a project of planting trees along the Great Wall of China, gathering 4,000 people to plant 400,000 trees. PUBLIC DOMAIN

A Fresh Start from Burnt-out Fields in Postwar Japan

Approximately 67.2% of Japan’s land is forest, covering 25.05 million hectares. Around 41% of this is planted forest. Planted forests have become widespread in order to ensure the ongoing reproduction of timber resources, growing trees for felling, then after felling, planting trees again.

From 1950 to 1970, large numbers of conifers were planted in forests across the country in order to generate materials for wooden houses to meet the demand for housing due to over-thinning and the destruction of residential and other buildings by fire in the air raids during the Second World War and demobilization from the battlefield. Demand was further compounded by the surge in migration from rural districts to urban areas during the period of high economic growth. This has been supported by the afforestation promotion campaign and the lifting of import bans that continue to this day. In 1950, the first National Arbor Day was held for the afforestation of national land, and the Green Fund was launched. Afforestation and forest protection became a national movement. In response to increasing demand, timber imports were liberalized in 1960. Over the last twenty years, planted forests have increased by approximately 30% to 10 million hectares, while natural forests have decreased by approximately 15%.

However, when the timber supply increases due to imports, the price of domestic timber begins to fall. Japanese forests are often located on steep slopes, making export costs after logging high, so it became uncompetitive against cheap imported timber. As a result, the size of the forestry industry workforce, numbering around 500,000 in 1955, continued to decline due to aging and a lack of successors to around 50,000 in 2015. Ironically, Japan’s stock of forest continues to increase as a result.

Nevertheless, Japan’s lumber self-sufficiency rate is low. In 1955 it was 96.1%, but for the reasons mentioned above it steadily declined, falling to 18.8% in 2002. In 2015, it recovered to 33.2% due to the government’s forest policy. However, it will be an uphill struggle to attain the goal of 50% set by the government due to the fact that, while cheap imported timber and planted forests were originally intended to supply residential building materials, the trees grown were largely Japanese cedar and cypress, which have limited application as timber.

The challenges of Japan’s forests lie in the regeneration of forestry, the maintenance of planted forests, the development of human resources and the revitalization of the market.

Japanese People and the Forests

The Japanese have traditionally exploited wood in their everyday lives. As timber, and as sacred trees, they have utilized every part of the tree, from branches to bark. The timber remnants are used to make disposable chopsticks and toothpicks. In order to protect the culture of trees, the cycle of logging and planting has continued without interruption.

One planted forest that is known for its beauty is a forest of Kitayama cedar trees in Kita Ward, Kyoto (pictured top). With a history going back more than 600 years, the timber has been used as a material for tokobashira (alcove posts) in famous tea-houses and other traditional houses.

Kitayama cedar is famous for being featured in the work of one Japan’s foremost painters of the twentieth century, Higashiyama Kaii (1908–1999) and in the novel The Old Capital by Nobel Prize-winner Kawabata Yasunari (1899–1972).

Japan has no mid- to high-rise wooden structures such as those found in Scandinavia. However, it does have the five-story pagoda of Horyu-ji temple, the world’s oldest surviving wooden structure.

Many Japanese temples and shrines are surrounded by beautiful trees and are known for the beauty of their approach roads lined with forests. Chuson-ji temple in Iwate, Nikko Toshogu shrine in Tochigi, Meiji-jingu shrine in Tokyo, Ise-jingu grand shrine in Mie, Shimogamo-jinja shrine in Kyoto, Enryaku-ji temple on Mount Hiei in Shiga, Izumo-taisha grand shrine in Shimane, and Kamishikimi Kumanoimasu-jinja shrine in Kumamoto are just some examples. Mount Koya, the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage trails, and the 88 Temple Pilgrimage in Shikoku are also set among beautiful forests. Most shrines across Japan too are surrounded by trees called “sacred groves,” which have become part of the local landscape as well as providing a home for flora and fauna.

“House trees” are planted around houses or on a hill at the back of houses for protection, here in Nanto City, Toyama Prefecture PUBLIC DOMAIN

Traditional Japanese houses have also used trees as windbreaks, snowbreaks, and sandbreaks. These house trees, such as Japanese cedar, are planted around houses or on a hill at the back of houses for protection. Also, on the Japanese coastline there are many pine forests surrounded by sea, which not only serve as windbreak forests, sandbreak forests, and tide-water control forests, but also create beautiful landscapes. A classic example is the pinery of Miho, which along with Mount Fuji was registered as a World Heritage site. Its beauty has been celebrated in waka poetry and haiku, and has been the theme of numerous ukiyo-e paintings, including Nihonga. In addition, haiku master Matsuo Basho (1644–94) composed haiku at Matsushima, Chuson-ji temple, and Risshaku-ji temple in Yamagata, and the sumi-e ink painter Sesshu (1420–1506) depicted Ama-no-hashidate with its beautiful pinery in his View of Ama-no-hashidate. It is no exaggeration to say that the beautiful scenery of trees characterizes the Japanese landscape.

Recovery from Natural Disaster

However, the large tsunami that struck eastern Japan in March 2011 washed away that beautiful view in an instant, along with many lives. Japan received widespread support from around the world, and recovery and reconstruction began. Measures such as tide embankments, the recovery and regeneration of coastal disaster prevention forests, and the utilization of timber for housing reconstruction have been promoted as the basis for protecting lives and livelihoods. These initiatives have included a range of participants and projects, large and small, to help those impacted by the disaster to recover emotionally, by restoring the occupations on which they prided themselves and the beautiful scenery of the region.

Millennium Hope Hills, established using the Miyawaki method of planting in Iwanuma, Miyagi Prefecture

For example, the aforementioned Miyawaki conducted a field survey in the affected area immediately after the earthquake struck and called for the creation of a forest tide embankment. His wish was to protect life and at the same time restore forests to something more than windbreak and sandbreak forests. From a thorough field survey, he established the “Miyawaki method” of planting. This entailed identifying trees with the most stable resilience that grow naturally in the wild, cultivating their seedlings, and then letting nature take its course, eventually growing into a natural forest-like state. This contributed to the regeneration of forests both in Japan and overseas. Miyawaki has been working on a project to collect acorns, then cultivate seedlings and plant trees over approximately three years in Kanagawa Prefecture, where Yokohama National University is located. Something of this resonates with The Man Who Planted Trees.

In April 2011, one of Japan’s leading animators, Takahata Isao (1935–2018), attended a press conference on the special exhibition L’Homme qui plantait des arbres by Frédéric Back (1924–2013), to be held at the Museum of Contemporary Art Tokyo on July 2–October 2, 2011.

Takahata said that having been struck by the unprecedented Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami as well as the terrible nuclear disaster, it is time that Japan took a new look at Back’s work.

“L’Homme qui plantait des arbres depicted a lone man who silently planted trees in a desolate mountainous district and restored life to the earth,” he said. “As we work hard together in the future for recovery, overcoming a host of difficulties along the way, it is a powerful source of encouragement to us and is certain to offer us hope.”

The following is an extract from The Man Who Planted Trees.

All that had changed, even to the air itself. In place of the dry, brutal gusts that had greeted me long ago, a gentle breeze whispered to me, bearing sweet odors. A sound like that of running water came from the heights above: It was the sound of the wind in the trees. And most astonishing of all, I heard the sound of real water running into a pool. I saw that they had built a fountain, that it was full of water, and what touched me most, that next to it they had planted a lime-tree that must be at least four years old, already grown thick, an incontestable symbol of resurrection. (Translated by Peter Doyle)

You cannot recover what you lost exactly as it was, but you can regenerate it in a new form.

Regeneration Process

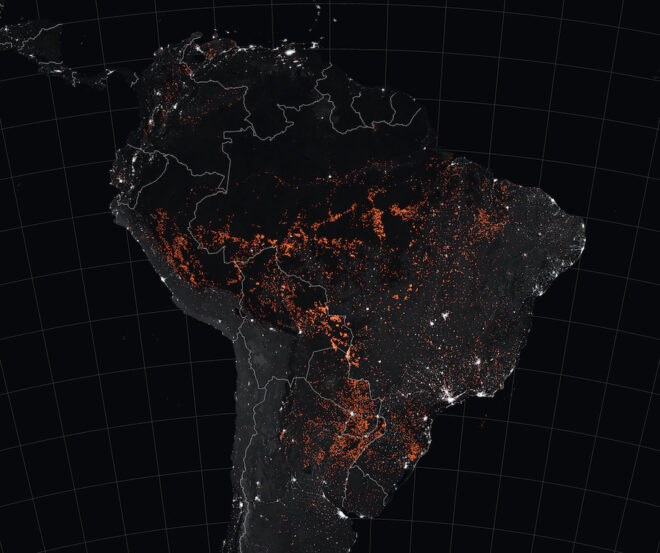

Satellite images showing the fires (orange dots) raging in the Amazon rain forest, August 15 to 22, 2019. Source: https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/images/145498/uptick-in-amazon-fire-activity-in-2019

I recall that the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (the Earth Summit) held in Brazil in 1992 achieved a global consensus on forests, adopting the Non-Legally Binding Authoritative Statement of Principles for a Global Consensus on the Management, Conservation and Sustainable Development of All Types of Forests (Rio Forest Principles). At the same time, Agenda 21-Chapter 11 adopted at the Summit included “Combating Deforestation,” declaring the following objectives.

a. To strengthen forest-related national institutions, to enhance the scope and effectiveness of activities related to the management, conservation and sustainable development of forests, and to effectively ensure the sustainable utilization and production of forests’ goods and services in both the developed and the developing countries; by the year 2000, to strengthen the capacities and capabilities of national institutions to enable them to acquire the necessary knowledge for the protection and conservation of forests, as well as to expand their scope and, correspondingly, enhance the effectiveness of programmes and activities related to the management and development of forests;

b. To strengthen and improve human, technical and professional skills, as well as expertise and capabilities to effectively formulate and implement policies, plans, programmes, research and projects on management, conservation and sustainable development of all types of forests and forest-based resources, and forest lands inclusive, as well as other areas from which forest benefits can be derived.

The Rio Forest Principles were followed in 1993 by the “Montréal Process,” by which twelve countries with temperate forests excluding Europe (Canada, USA, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, New Zealand, Australia, Korea, China, Russia, Japan) agreed to begin formulating common criteria and indicators to promote sustainable forest management.

Many people apparently think that The Man Who Planted Trees is non-fiction or do not know that it is fiction. An anecdote has it that Back learned that it was fiction during the animation production process, and that when Takahata spoke with Back about the finished animated film, he was still convinced that it was “true.”

It may be fiction, but it still contains a truth that spurs people to action. Right now, I hope that the Amazon rain forest fires are extinguished and that the process of regeneration thereafter will be as swift as possible.

MIZUNO Tetsu is a freelance writer.