Japan’s “Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics,” which draws on decades of experience in the waste management field, will come under the spotlight in June as discussions at the G20 Summit in Osaka turn to the rapidly intensifying problem of marine litter.

[This article appeared in the May/June 2019 issue of the The Japan Journal, prior to the meeting of G20 environment and energy ministers in Karuizawa on June 15 and 16 in which the ministers agreed to adopt an international framework to reduce marine plastic waste.]

The G20 Osaka Summit will be held from June 28 to 29, 2019. This will be the first G20 held in Japan, and ministerial meetings will take place in eight Japanese cities. A key topic of discussion during the meeting will be the ocean plastic problem, previously raised as an issue at the 2018 G7 summit.

Japan has deep experience in the area of environmental pollution, having overcome domestic pollution problems arising from industrial and household waste, developed environmental technology, built recycling systems and set up legal frameworks. As well as presenting information regarding its own ongoing Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics, as the G20 host country this year, Japan must mediate discussion and show its contribution to international society.

Postwar Light and Darkness

Postwar Japan experienced both the “light” of high economic growth and the “darkness” of water and air pollution. And the light was as strong as the darkness was deep. From 1955 to 1973, Japan averaged an economic growth rate of over 10%, and by 1968 it had risen to become the world’s second-largest economy. Voracious economic consumption symbolized a feeling among the Japanese population that they were all middle-class. Every citizen of Japan wanted to buy what was known as the “Three Sacred Treasures” of television, washing machine and refrigerator. To these was added the three “C”s: color television, cooler and car. The whole of Japan was filled with energy and there was no stopping the flood of mass production and mass consumption.

Needless to say, however, mass production and mass consumption equal mass waste, and they led to pollution problems that affected life and dignity. Amid this suffering, pollution problems were overcome thanks to the intelligence and hard work of government and people, via numerous citizens’ movements, legal structures and technological development. Out of this pain, Japan gained such things as environmental technology (notably, energy saving technology) and the provision of environmental regulations to deal with pollution. True measures to deal with mass waste, however, lagged behind, and real measures only began in the 1990s.

Legal Structures

In 1991, the Act on the Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources (currently, the Law for Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources) was enacted as a basic measure to make the growing volume of waste a recyclable resource and effectively reuse it. In 1993, the Basic Environment Law was promulgated and put into effect as the core of Japan’s environmental policies. In 1995, the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law was enacted (passed June 1995, partial entry into force April 1997, and full entry into force in April 2000.) Then in June 1998, the Home Appliance Recycling Law was put into effect.

In 1991, the Act on the Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources (currently, the Law for Promotion of Effective Utilization of Resources) was enacted as a basic measure to make the growing volume of waste a recyclable resource and effectively reuse it. In 1993, the Basic Environment Law was promulgated and put into effect as the core of Japan’s environmental policies. In 1995, the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law was enacted (passed June 1995, partial entry into force April 1997, and full entry into force in April 2000.) Then in June 1998, the Home Appliance Recycling Law was put into effect.

The aim of the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law was to promote the effective reuse as resources of glass containers, PET bottles, paper containers and packaging, and plastic containers and packaging. Also, the Home Appliance Recycling Law aimed to promote the effective reuse of resources via the recycling of home electrical appliances and the reduction of waste materials.

The aim of the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law was to promote the effective reuse as resources of glass containers, PET bottles, paper containers and packaging, and plastic containers and packaging. Also, the Home Appliance Recycling Law aimed to promote the effective reuse of resources via the recycling of home electrical appliances and the reduction of waste materials.

In June 2000, the Basic Law for Establishing the Recycling-based Society brought together these laws and Japan’s other waste and recycling policies. The principles behind it were expressed through the three “R”s concept: Reduce, Reuse and Recycle. In 2006, the amended Containers and Packaging Recycling Law also encouraged the promotion of the three Rs for container packaging waste, while setting rules to reduce containers and packaging such as checkout bags.

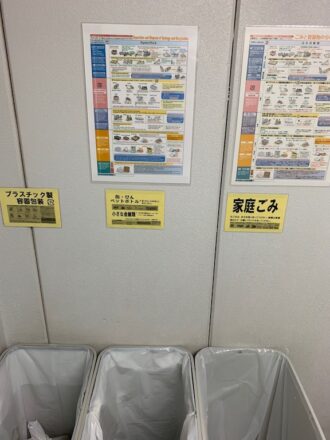

These world-leading initiatives changed the everyday lives of Japanese people. Household garbage now needed to be separated into narrow categories such as combustible garbage, non-combustible garbage, metal items, glass items, plastic containers (food trays, plastic bags etc.), PET bottles, glass bottles (empty health drink and dressing bottles), and paper packaging. This painstaking separation of items was helped by Japanese people’s traditional sense of mottainai.

These world-leading initiatives changed the everyday lives of Japanese people. Household garbage now needed to be separated into narrow categories such as combustible garbage, non-combustible garbage, metal items, glass items, plastic containers (food trays, plastic bags etc.), PET bottles, glass bottles (empty health drink and dressing bottles), and paper packaging. This painstaking separation of items was helped by Japanese people’s traditional sense of mottainai.

“Mottainai” loosely means “wasteful” but in its full sense conveys a feeling of awe and appreciation for the gifts of nature or the sincere conduct of other people. There is a trait among Japanese people to try to use something for its entire effective life or continue to use it by repairing it. In this caring culture, people will endeavor to find new homes for possessions they no longer need. The late Dr. Wangari Maathai, who was born in Kenya and was the first person working in the environmental field to receive the Nobel Prize for Peace, is known for coming across this term in 2005 and popularizing its spirit along with the three Rs.

Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics

After the Containers and Packaging Recycling Law was fully put into force in April 2000, the volume of waste definitely trended lower. The problem, however, was the plastic garbage that still accounted for around 40% of household garbage (44.1% in fiscal 2016).

Although in 2016 the recycling ratio of plastic reached 84%, which was more than the EU’s 73%, it was still not enough.

Aiming for a recycling-oriented economy, the EU pushed forward world-leading initiatives, such as regulations and laws governing ten types of disposable plastic products and fishing equipment. There were fears that household waste would be carried into the sea, become tiny pieces of plastic, then the chemical substances contained and absorbed within them enter the food chain and impact on the ecosystem.

Calls for setting rules and targets for disposable plastic products in developing countries also became stronger. China had accepted the imports of waste plastic as a reusable resource, but in December 2018 it prohibited the import of waste plastic and ASEAN countries are also now strengthening their import regulations. It is becoming increasingly necessary for countries that previously exported waste plastic to these regions, such as Japan and the United States, to process this waste domestically. Japan, as well as other countries, is in danger of becoming saturated in waste plastic, so a range of measures are needed.

The response from Japanese industry includes: paper materials companies boosting work on developing products to replace plastic straws and checkout bags; and, in the biodegradable and biomass plastic fields, research and development and joint projects with overseas counterparts by companies that possess world-leading technology. Start-ups are also accelerating their efforts to develop new materials. Behind these developments are the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These initiatives seek to address SDG number 12, and the public and private sectors in Japan are jointly and actively engaged in this.

Detailed instructions for the disposal of waste in English and Japanese above bins on a floor of a Yokohama apartment block. [Advisory produced by the City of Yokohama Resources and Waste Recycling Bureau.]

In March 2019, the Central Environment Council of the Ministry of the Environment compiled its response regarding the Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics and presented them to the Minister of the Environment. Having received this response, the government will formulate its Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics before the June 2019 G20 Summit.

Notably, the response set higher targets than the ocean plastics charter raised at the 2018 G7. (See Milestone 1, 3, 5 and 6 in the Table.)

The response features: “actionable support measures for developing countries (international cooperation and business development through exports of order-made packages of Japanese soft infrastructure, hard infrastructure and technology) [and] the setting-up of a global-scale monitoring and research network (research into ocean plastic distribution and effect on ecosystems, standardization of monitoring methods, etc.).”

The following text is from the section titled “Use International Frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)” in the The 3rd Basic Plan on Ocean Policy decided by the Japanese Cabinet in May 2018.

To protect the irreplaceable ocean environment, we will establish appropriate marine reserves, protect fragile ecosystems, prevent ocean pollution, take steps against marine litter, and respond to climate change under international frameworks such as the SDGs. We will also adopt preventative approaches to contribute to the protection of the marine environment while appropriately reflecting the Japanese way of thinking about marine protection and the sustainable development and use of the ocean based on scientific knowledge.

Japan has already acquired technology, and although it is important to establish a waste plastic market and tie that to economic growth, above all the nation needs principles that go beyond that, along with actionable and concrete near-term measures.

MIZUNO Tetsu is a freelance writer.

Milestones toward actualizing the Resource Circulation Strategy for Plastics<Reduce>

<Reuse and Recycle>

<Recycling use and Biomass plastics>

|

A line of trash cans encouraging sorting at the seaside Rinko Park in Yokohama