Kimura Kan, professor at the Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies at Kobe University, discusses Japan-Korea relations today against the background of the COVID-19 pandemic and administration change in the Republic of Korea and United States.

COVID-19 defined 2020. As every nation in the world struggled mightily to deal with the pandemic, the public’s attention was diverted from matters of international affairs. That was, of course, true of Northeast Asia, ground zero for the pandemic. The North Korea crisis and the US-China conflict that had dominated the world’s attention in 2018 and 2019 were put on the back burner. In those circumstances, relations between Japan and South Korea also remained stuck. Travel between the two neighboring countries — which at one time exceeded 10 million people every year — ground to a complete halt. Summer in both nations was often marked by rancorous public debate of a range of historical issues, but that too passed without a peep.

COVID-19 is still with us in 2021, with the damage from the “third wave” threatening to overshadow the two “waves” that went before. Now, however, vaccination campaigns have begun in many nations, and people are anxious for them to show results. As international relations shift from “frozen” to “thawing,” opportunities for real change are opening once again.

The switch from President Trump to President Biden was particularly significant, because it signaled a major shift in political power. America’s foreign policy is on the threshold of a major change. Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who was known for revisionist statements regarding historical issues, left the stage. For South Koreans, who strongly disliked Abe, this was good news. The South Korean government has been trying a variety of approaches to Japan.

Meanwhile, as the Biden administration has been stepping up criticism of China, people are interested to know what approach it will take in dealing with the still noxious relationship between Japan and South Korea. This is more of a concern for South Korea than it is for Japan. That is because, toward the end of the Obama administration, when Biden was vice president, the United States put strong pressure on Japan to resolve the issue of the “comfort women,” which was the most rancorous historical issue in Japan-South Korea relations at that time. In the ensuing agreement, South Korea relinquished its legal demands for compensation over the “comfort women” problem. It bears repeating that this stands in direct contradiction to Seoul’s earlier demands for financial compensation from the Japanese government. Those demands were, however, reaffirmed on January 8, 2021 by the Seoul Central District Court. If the US presses the South Korean government to abide by the earlier agreement, the South Korean government will be in a real bind.

A scenario of this sort would be an additional burden on Seoul. The important thing to note here is that the South Korean constitution recognizes the jurisdiction of international law, stating: “Treaties duly concluded and promulgated under the Constitution and the generally recognized rule of international law shall have the same effect as the domestic laws of the Republic of Korea.” The prevailing view is that, in the event of a contradiction between the two, international law is subordinate to the constitution.

However, in this interpretation, if a decision by the judiciary based on the constitution contradicts a treaty concluded by the government, then the government is bound to be caught in a dilemma between the requirements of the judiciary and the demands of the government that is counterparty to the treaty.

A point that should not be overlooked here is that since the start of this year, the situation is now very different from what it was before. That is to say, the antagonism between Japan and South Korea that has existed since January 1992, as manifested in the problem of the comfort women, and the problem of the former forced laborers, has revolved mainly around differing interpretations of the Agreement Between Japan and the Republic of Korea Concerning the Settlement of Problems in Regard to Property and Claims and Economic Cooperation. It was the South Korean government whose interpretation changed the most in the period from 1992 to 2012, forcing the two governments to strive mightily to make the needed adjustments. That is because, whether precipitated by a decision of the executive branch or not, it was the executive branch that was in a position to make the adjustments.

In 2012, however, the situation changed dramatically when South Korea’s Supreme Court ordered the High Court to reconsider its decision in the case of the former forced laborers. That was because the judiciary had become the main “change agent” regarding how the case was interpreted. As a result, under pressure from the judiciary, the South Korean government lost its room to maneuver, in the interest of “respecting the decisions of the judicial branch,” and the situation was effectively left as it stood.

That said, with respect to the Japan-Korea Agreement on Claims, which was the subject of the debate, this kind of situation was only possible because the agreement had been created through a long process of negotiations and diplomatic compromises between the two nations. By contrast, the 2015 “Comfort Women Agreement” took the form of a joint declaration by the foreign ministers of the two nations, and was a much simpler agreement that had been the result of a much shorter process. In view of the importance of US-South Korea relations, as long as the South Korean government recognized the legal force of this agreement [Comfort Women Agreement], if it came under strong pressure from the US to honor it, it would have virtually no power to contest the “interpretation.”

The problem for the South Korean government is whether the Biden administration will pressure Japan and South Korea to improve their bilateral relations, and in particular whether it will do so within the framework of compliance with the “Comfort Women Agreement” and other factors that surrounded historical issues around the time of the end of the Obama administration.

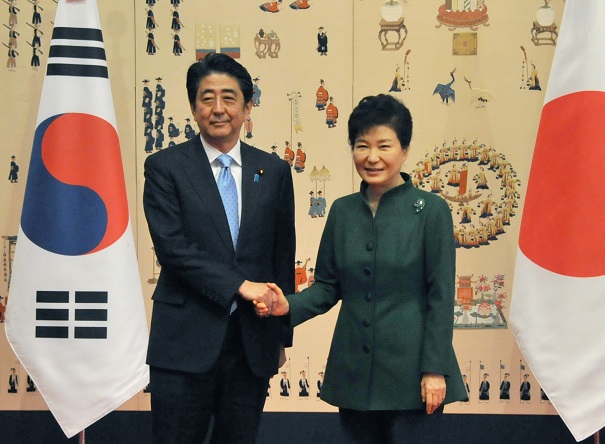

Then Prime Minister Abe and then President Park shake hands before the Japan-ROK Summit Meeting held in Seoul, November 2, 2015. CABINET PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICE PHOTO

It would be useful to recount now the process that led up to the 2015 Comfort Women Agreement. My understanding is that the main points were: In December 2012, Japanese Prime Minister Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye were both conservative politicians, with similar worldviews, who were elected to office about the same time. Some people believed it would be easy for them to build an amicable relationship; however, as we all know, this was not to be. Relations between Japan and South Korea grew significantly worse, as a direct result of South Korea’s rigid stance. From the beginning of his administration, Abe was sending friendly messages, but President Park was interested only in radical remedies for the comfort women problem. She refused to meet with Abe one-on-one. As Park kept repeating to other nations the same message demanding a solution for the comfort women problem, this elicited a sharp response from both the Japanese government and the people of Japan.

In my own humble opinion, the South Korean government’s position rested on two basic assumptions. The first was that the US and other nations would support the South Korean side on this issue. That was because the international community had previously been alarmed by statements Abe had made that were regarded as “revisionist,” combined with a perception that the Obama administration would not be receptive to them due to its stance on human rights. The second was Seoul’s expectations regarding US-China relations. At the time, South Korea was moving ahead with globalization, and the US and China were in a state of mutual interdependence. For that reason, the prevailing view was that, even if a superficial, temporary, localized confrontation should arise between the two nations, smooth relations would be restored in the end. In these circumstances, Park aligned herself with the US, and also got closer to China, in an attempt to leverage South Korea’s relationship with these two superpowers in dealing with Japan.

When these two assumptions crumbled, however, the Park administration’s prospects also collapsed. One reason the assumptions did not pan out was Abe’s apparent affirmation of his “historically revisionist” statements. One particularly important point was the problem of his visit in December 2013 to Yasukuni Shrine, where Class-A war criminals condemned by the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal are enshrined. Since the US had played a central role in that tribunal, an official visit to Yasukuni was tantamount to a provocation of Washington. The US Embassy in Tokyo responded to Abe’s visit with the unusual step of a critical statement, “The United States is disappointed that Japan’s leadership has taken an action that will exacerbate tensions with Japan’s neighbors.”

Abe changed course after that, however, and refrained from making any further visits to Yasukuni. Then in 2015, Abe abandoned his promise to revisit the Kono Statement regarding the comfort women issue. In August of that year, he released the “Abe Statement,” acknowledging the “wrong course” Japan had taken during World War II. Through this process, Abe succeeded in quelling some of the criticism of himself personally as a “historical revisionist,” and restored some faith in Japan among the community of nations.

Then Prime Minister Abe speaks at a press conference following the signing of the Japan-ROK General Security of Military Information Agreement (GSOMIA), November 22, 2019. CABINET PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICE PHOTO

Then in early 2014, tensions in the South China Sea escalated, and the Obama administration toughened its stance against China. The US pressured Japan to expand its area of maritime defense, and pressed South Korea to deploy THAAD (Terminal High-Altitude Aerial Defense) missiles. The US wanted Japan and South Korea to conclude the GSOMIA (General Security of Military Information Agreement), to pave a smooth route for military cooperation. At the time, relations between Japan and South Korea had soured to the point where the leaders of the two nations could not even schedule a summit, but they came under strong pressure to make improvements.

It was around this time that President Park made a serious misstep. Even in 2015, the South Korean government did not break off its efforts to get closer to China. Washington grew exasperated with President Park. When she traveled to Beijing for the military parade marking the 70th Victory in September 2015, that was sensational news.

In 2015, the US pressured both Japan and South Korea, but particularly South Korea, to improve their bilateral relationship. The upshot of this was pressure on the Park administration to reach some compromise on the comfort women situation, i.e., pushing it to the “Comfort Women Agreement.”

Looking back now on the situation at that time, it is clear there were several factors leading Washington to pressure Japan and South Korea, and particularly South Korea. First among these was the standoff between the US and China, and particularly the national security issues involved. Unlike economic relations, which are governed by sometimes overlapping “alliances” defined by agreements such as the TPP, RCEP, and other free trade agreements (FTAs), in national security issues, both Japan and South Korea were of prime importance as allies of the United States, hosting large numbers of US troops, on the same scale as Germany.

The second important thing was that at that time, the US had genuine concerns surrounding national security issues in this region: the Japan-South Korea GSOMIA, and the deployment of THAAD missiles in South Korea. For America as a superpower, problems surrounding China, even if they were critically important, were no more than part of the international issues it had on its plate. In terms of its importance for US national security, South Korea’s naval power was less than Japan’s, and it had limited capacity to project force beyond the Northeast Asian region. That gave the US some urgency in pursuing improved relations between Japan and South Korea.

The third important factor was the concern that South Korea’s diplomatic activities might affect the power balance between the US and China. In other words, while Washington still regarded Seoul as an important ally, it may have believed that allowing Seoul to continue its efforts to grow closer to Beijing could give a green light for nations in Southeast Asia and other US allies to cozy up to China, which would have a big influence on both economic and national security relations. That meant Washington had to stop Seoul, and one way it could do this was through a loyalty test on the comfort women agreement.

The fourth factor was that, at that time, Japan had moderated its stance on matters of interpreting history in hopes of rekindling dialog with South Korea, but Seoul had remained adamant in refusing to participate in talks. Naturally enough, the US concluded it was Seoul’s obstinacy that was causing the standoff. It was toward the end of the Obama administration, as the US was pressuring both Japan and South Korea to improve relations, but putting more pressure on Seoul, that the comfort women agreement was signed in 2015, and the Japan-South Korea GSOMIA in 2016.

To what extent are conditions today the same as they were then? The first thing that is clear is that the US and China are still at loggerheads. US-China relations are much worse now than they were in the latter years of the Obama administration. President Trump took a very hard-nosed stance on China, and his successor President Biden appears to be maintaining that course.

It is important to note here that US criticism of China now appears to be more focused on economic and human rights issues, rather than national security. The White House summary of the first phone call between Biden and President Xi Jinping of China, on February 10, 2021, frames economic and human rights problems as matters of national security: “President Biden underscored his fundamental concerns about Beijing’s coercive and unfair economic practices, crackdown in Hong Kong, human rights abuses in Xinjiang, and increasingly assertive actions in the region, including toward Taiwan.” Of course, the mention of Taiwan here means Biden is not ignoring security issues. One more important thing: apart from GSOMIA matters, the US is not currently exerting any major tangible pressure on either Japan or South Korea. The main reason for that is that the Trump administration basically declined to deal with national security policy at all. It is well known that since the start of this century, the US has been engaged in a realignment of its military forces, in an effort to maintain its international influence with more limited resources. “Force realignment” of course also means rethinking America’s relationships with its allies. Debate has focused on how America should use its allies to maintain an effective balance of military might. In the big picture, the argument can be made that the debate over the role of Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force in the East China Sea and the South China Sea, and the deployment of THAAD missiles in South Korea, were part of this “reallocation of military forces” policy.

The Trump administration, however, because of its strongly isolationist bent, did not put high priority on relationships with allies. Its main aim was to lessen the burden of America’s military commitments, and its main focus was to pressure US allies to increase their share of the cost of keeping US troops in their countries. It even raised the possibility that the US would ultimately reduce its military presence overseas. Since the start of the Biden administration, the US has pivoted once more. It is now in a phase of rethinking its basic policies on national security matters, including strengthening relationships with allied nations. It may take some time yet before the US gets around to placing concrete demands on Japan and South Korea.

It would seem that improvement of the relationship between Japan and South Korea – while it may be of importance at some abstract level in the medium to long term — is not a problem of concrete importance in the near term, at least for the time being. One other important point: the situation on the Japan-South Korea side has also changed considerably in the past six years.

In this regard, the most important point is that the offense-defense situation has changed. In 2015 it was South Korea that took a hard public stance on historical issues, and refused to engage Japan in dialog, and thus a softening in its attitude was demanded. Since 2018, meanwhile, it has been Japan that is refusing to engage in dialog. At least in terms of what is visible from the outside, South Korea is the one that is more open to discussion.

The second major recent development is that the South Korean government has grown more cautious regarding China. It seems people in Japan often think the Moon Jae-in government is leftist and favors China, but the truth is that from the outset, Moon has been quite restrained in his approach to China. In North Korea issues, which are the Moon administration’s top diplomatic priority, Moon seems to be consistently aligning himself more with the US than with China. Clearly this is in reaction to the failures of his predecessor Park.

Then US Vice President Mike Pence joined then Prime Minister Abe and ROK President Moon for a photo session following the Japan-ROK Summit Meeting of February 9, 2018 before the Opening Ceremony for the Olympic Winter Games in Pyeongchang. CABINET PUBLIC RELATIONS OFFICE PHOTO

The third and most important thing is the “experience” Japan and South Korea had with the US under the Trump administration. Under the Trump administration, not just Japan and South Korea but countries around the world grew skeptical of US stability, due to its neglect of relationships with allies, the commotion that surrounded its foreign relations, and the turmoil that reined during the transfer of power. In other words, as long as the US is stable, people may have faith in its future-oriented promises. They may also think that if they oppose US wishes, they may feel pressure from its tremendous power, to go along. In these circumstances, people may feel they might gain some benefit from responding positively to America’s occasional demands, and they may expect long-term disadvantages from resisting them.

But if instability in America were to continue, we would no longer be able to make the same calculation or hold the same expectations. As both Japan and South Korea keenly experienced in negotiations over sharing the burden of the cost of hosting US military bases, it is only sensible to buy time in response to adverse demands and wait for the other side to change their mind.

If that is the case, once the world becomes “unfrozen” from COVID-19, it seems fair to expect that international relations in general, and Japan-South Korea relations in particular, will be far different from what they were before. We should remain a bit guarded about what is about to happen.

KIMURA Kan is a professor at the Graduate School of International Cooperation Studies, Kobe University.