Working alongside the National Civil Police (PNC) in Guatemala, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has built on its success in Brazil to implement a “Project for Strengthening of Police Human Resources through the Promotion of Community Police Philosophy” that has achieved remarkable results.

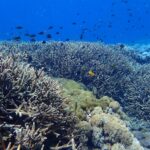

Officers of the Civil National Police (PNC) visit a Japanese school in Guatemala City, June 2019

COURTESY OF JICA

In Guatemala, a military coup d’état in 1954 led to the outbreak of a civil war in 1960 in which tens of thousands of people were killed before the government and guerrillas signed peace accords in 1996. Subsequently, crimes perpetrated by drug syndicates and gang groups have become a serious problem. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), the incidence of murder cases per 100,000 in Guatemala stood at 23.3% in 1999, but rose to 45.4% in 2009. Subsequently, the rate decreased to 27.3% in 2016. How to improve public safety remains a major issue in the Central American country.

In Guatemala, the national police, which was seen as essentially an organization of civilians in the military service, was broken up in 1997 after the end of the civil war, and the National Civil Police (PNC) was established for the sake of civil security. In 2014, the Police Model of Integral Community Security (MOPSIC) was introduced to the PNC, and crime control through coexistence, cooperation and collaboration between the police and local communities was established as a national strategy.

To assist, Japan has provided the PNC with audio-visual equipment, vehicles, computers and other items for use in police schools, through grant aid. From 2008 to 2013, Japan had provided assistance to the Brazilian police’s training programs that were implemented with the participation of a total of about forty PNC-related personnel.

Since 2016, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has implemented a “Project for Strengthening of Police Human Resources through the Promotion of Community Police Philosophy,” making the PNC its counterpart.

“MOPSIC is about introducing the concept of community police, and the activities the police should conduct in the local community to realize the concept was not explained. That is why the local police were not prevalent,” says Marta Ventura, a project officer at JICA’s Guatemala office. “The purpose of our project is to foster and nurture human resources who carry out community police operations and to promote those human resources based on MOPSIC.”

Project activities were conducted especially at four pilot police stations in Chinautla City and San Pedro Ayumpuc City, adjacent to Guatemala City, the capital. The total population of districts over which the four police stations have jurisdiction was about 120,000, and the total number of police officers was about 200. For this project, JICA provided materials and equipment, including personal computers, ten motorcycles and twelve surveillance cameras, sent Brazilian experts to Guatemala, and provided support for training programs in Japan, Brazil and Guatemala.

Since 2000, JICA has supported the promotion of community police in Brazil in collaboration with the National Police Agency and has contributed to improving public safety in Brazil. Third-country training programs to spread this experience throughout Latin America were implemented in Brazil, and trainees from Guatemala and other countries participated in the programs.

Eight training programs were implemented in Brazil during the years between 2016 and 2019 with the participation of a total of 100 Guatemalan trainees. In these training programs, lectures and on-the-job training were conducted so that participants could study the Brazilian community police. In addition, ten training programs were implemented in Guatemala with the participation of a total of about 1,200 police officers from around the country as well as from pilot police stations. In these training programs, the participants acquired knowledge of the community police using DVDs or learned customer services in collaboration with a vocational training school.

“The activity of the Brazilian community police could be applied to Guatemala as well,” says Ventura. “The training programs in Brazil provided a significant impetus to Guatemalan police officers.”

As part of the project, the police worked on a range of activities, including visits to shops, meetings with local leaders and city government officials, school lectures and traffic safety programs.

The Policia Tu Amigo Program was a crime prevention program that aimed to make young people feel a sense of closeness and familiarity toward the police and prevent them from becoming involved in crime syndicates. This program was implemented in eight elementary schools for three months with the participation of around 660 people.

The traffic safety program was implemented in seven elementary schools eight times with around 220 participants. In addition, pilot police stations spontaneously implemented eight police station visit programs in order to introduce the details of police work and promote knowledge of crime prevention with the participation of around 300 young people.

Moreover, forty events in which police station officers visited local communities with toys and communicated with children were also implemented with the participation of around 2,500 local citizens. Ex-participants who participated in training programs in Brazil also played a central role in setting up street lights, removing graffiti and picking up litter in cooperation with the local citizens and city government officials.

Furthermore, police officers planted 100 seedlings together with civil volunteers to support a city afforestation project implemented at the initiative of the mayor of San Pedro Ayumpuc City, where pilot police stations were located.

In addition, the police sought to proactively meet the requests of local citizens. For example, in response to citizens’ inquiries about the reason for the ban on selling alcoholic beverages after 10 p.m., the police held an explanatory meeting for the local people, explained that numerous crimes due to drinking were perpetrated in the evening and obtained the understanding of the local people.

Moreover, in a case where police stations received complaints about garbage, the police asked the city government’s section in charge of garbage administration to dispose of the garbage and also conduct a regular cleanup activity together with local citizens.

This broad range of activities contributed to building cooperative relationships between the police and local citizens. When the police made a plan for an event that involved donating used stuffed toy animals to poor children and distributed letters of invitation to the local community, they received information about gun holders from citizens. There were about 4,000 anonymous calls to provide information to police stations and police officers in 2016, but these calls increased sharply to about 16,000 in 2017. As a result, many gun holders and drug smugglers were arrested. According to data compiled by two police stations in Chinautla City, 162 people were arrested in 2017, and the number arrested rose to 233 in 2018. Meanwhile, the number of murder cases decreased from 49 in 2017 to 24 in 2018.

In addition, with regard to the results of a test on the level of understanding of MOPSIC that was conducted with 100 police officers selected from each police station, 47% of the police officers of the pilot police stations that had implemented community police training programs scored 76 or higher, and 24% of the police officers of the non-pilot police stations scored 76 or higher. The police officers of the pilot police stations scored an average of 74, and the police officers of the non-pilot police stations scored an average of 63, with a margin of more than ten. These results clearly show that the project helped the police officers to increase their capabilities.

“At the beginning of the project, many police officers did not know why the project was necessary. They thought that the activity of police officers was solely to catch criminals,” says Ventura. “But through training programs and community activities, those police officers learned to understand how important it is to work closely together with the local citizens to prevent crime and arrest criminals.”

Surveys of the citizens conducted in July 2017 and February 2019 revealed that their attitude toward the police had also changed. In 2017, some 27% of the respondents stated that they felt that public security was good or very good. This percentage rose to 71% in 2019. In addition, for the police’s treatment of local citizens who submitted a report of the damage to them, in 2017, 42% of the respondents stated that the police’s treatment was good or very good. This percentage increased to 67% in 2019. Regarding the presence of the PNC in the local community, in 2017, 46% of the respondents stated that it was large or very large. This percentage increased to 70% in 2019. As for the level of confidence in the PNC, in 2017, 24% of the respondents stated that they had confidence or strong confidence. This percentage rose to 56% in 2019.

Santa Isabel Police Station, one of the pilot police stations, received a letter of appreciation from the local citizens. In addition, on May Day in 2018, the local citizens, particularly children, visited Rio Azul Police Station to express their gratitude to the police for their service.

“In the past, the children used to be afraid of approaching the police. But now that the children have taken to the police officers, they often visit them. Their parents also provide the police with a range of information about crime,” says Ventura. “Before the start of the project, the police officers did not smile at the local citizens. But they now deal with the citizens with smiles on their faces.”

The project ended temporarily in July 2019. However, Phase 2 of the project, which is aimed at further promoting the community police, is now under review. The infiltration of the community police into local communities is expected to spread to many parts of the country, resulting in a virtuous circle in which more police officers trusted by local citizens are produced and better public safety is also achieved.

BY SAWAJI Osamu

Note: This article first appeared in the September/October 2019 issue of The Japan Journal.